South Africa’s Covid-19 state of disaster ended in late March 2022. The government is now looking to add some of the regulations used to manage the pandemic to existing law – the National Health Act.

The proposed changes are open for public comment until July. But controversy has not been far behind, and the amendments may be challenged in court. Scientists have also weighed in.

The Democratic Alliance (DA), the official opposition to South Africa’s ruling African National Congress, has also objected to the proposed regulations.

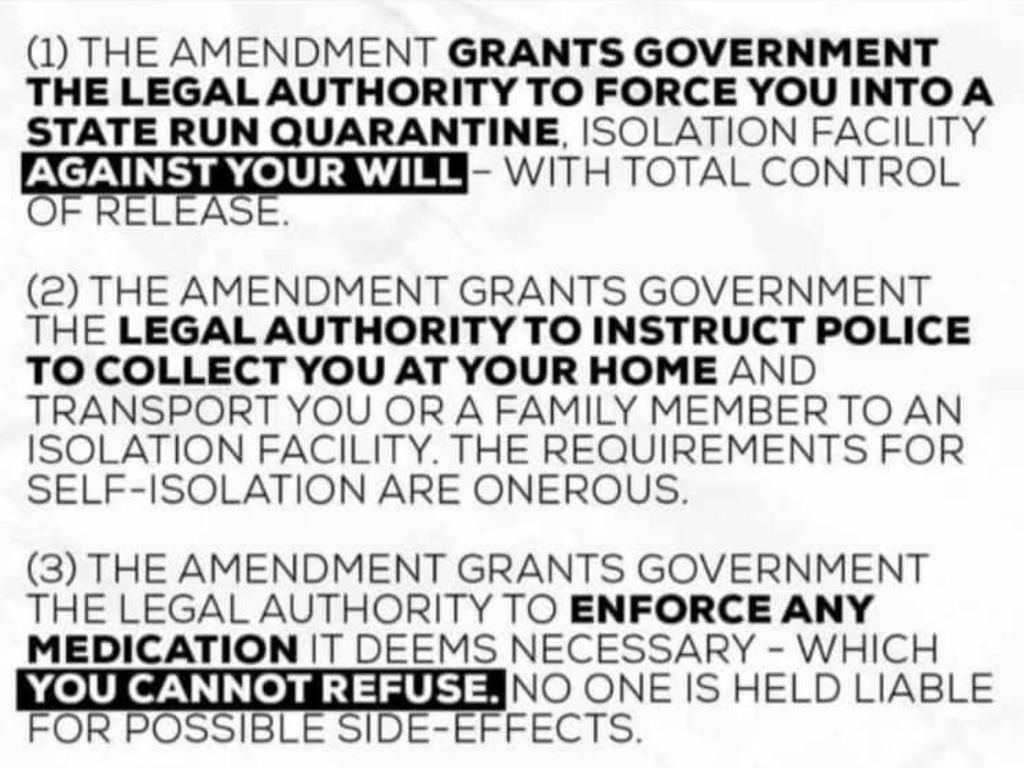

In early April the party tweeted: “🚨 How do you feel about forced Covid-19 vaccination? Don't let NDZ and the Minister of Health take away your power and normalise the State of Disaster!”

NDZ is shorthand for Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, minister of cooperative governance and often the public face of pandemic rules.

Michele Clarke, DA shadow minister for health, told Africa Check that the proposed regulations would be introduced “in addition to the existing legislation and regulations”, and would “include Covid-19 as a Notifiable Medical Condition”.

Michele Clarke, DA shadow minister for health, told Africa Check that the proposed regulations would be introduced “in addition to the existing legislation and regulations”, and would “include Covid-19 as a Notifiable Medical Condition”.

This would “allow the regulations to restrict and limit certain rights as well as force certain practices on those who test positive for Covid-19”, Clarke said. Claims about what the proposed regulations entail have also been spreading on WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter.

Africa Check recently debunked the claim that the regulations would override the right to privacy. In this analysis, we explain what the National Health Act is, and what the draft regulations would change.

Background: the National Health Act

The National Health Act (NHA), implemented in 2003, sets out laws that govern South Africa’s health system.

“It is national legislation that covers the operation of several areas of what we classically deem the ‘health sector’,” Petronell Kruger, senior researcher at the Wits University Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science, told Africa Check.

But the 2022 draft regulations are not amendments to the NHA itself. Instead, they are proposed changes to regulations added to the NHA in 2017. The existing regulations relate to the surveillance and control of notifiable medical conditions.

“The purpose of the 2017 regulations is to manage and control diseases identified as notifiable – as provided for in the National Health Act,” Leslie London, a professor of public health medicine at the School of Public Health and Family Medicine at the University of Cape Town, told Africa Check.

“The 2022 amendments are, presumably, intended to incorporate the specific measures deployed during the Covid-19 epidemic into the 2017 regulations.”

The health department defines notifiable medical conditions as diseases “of public health importance because they pose significant public health risks that can result in disease outbreaks or epidemics with high case fatality rate”. Covid-19 was declared a notifiable condition in May 2020.

The Health Act permits the addition of new regulations. This is known as deferred legislation, and allows for more responsive rule-making, Kruger told Africa Check.

Specialised areas of the law can be updated without relying on the sometimes slow process of passing new legislation through parliament, she said. “This is both normal and desirable in South Africa, as well as in other countries.”

Both the 2017 regulations and the proposed 2022 amendments are deferred legislation.

Experts told us that this means the proposed amendments can only be read in the context of the NHA and its 2017 regulations. “By law, a regulation may only operate within the confines created by the main piece of legislation that ‘birthed’ it,” Kruger said.

But what about claims that the regulations would allow the government to force vaccination or other medical treatment on citizens?

Proposed amendments wouldn’t revoke protections

The proposed regulations do say that someone who has, is thought to have, or has been in contact with anyone else with a notifiable medical condition – like Covid-19 – may be subject to certain requirements.

These include having to submit to medical examination, be admitted to quarantine, submit to “mandatory prophylaxis” or other treatment, and more.

Prophylaxis is the prevention or control of the spread of a disease, and includes measures like vaccination. The DA has quoted this wording as evidence that the regulations would allow mandatory vaccination.

“The only prophylaxis or treatment, at this stage, for Covid-19 is the vaccination,” Clarke told Africa Check.

But experts say the proposed regulations should be read as amendments to the existing regulations. This means they are subject to certain requirements.

London pointed out, for example, that the 2017 regulations “make it clear that the need for any mandatory action must be ‘determined on a case-by-case basis and tailored depending on the public health risk and individual circumstances of the person in question’”.

This restriction would also apply to new regulations. So enforcing any “mandatory action” such as vaccination or other medical treatment would require a court order.

“This naturally makes widespread application of this regulation impossible, and should allay a lot of fears that people might have about abuse of power as the courts are tasked with applying the Bill of Rights in all their exercises of power,” Kruger told Africa Check.

The DA’s Clarke acknowledged that “no legislation can ever overrule constitutional rights”. But she pointed out the Bill of Rights, section 36 of South Africa’s constitution, allows for rights to be limited in “reasonable and justifiable” cases. This was shown in the restrictions imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“It is not only the regulations that are concerning, but also the complete lack of oversight on the minister to implement any of these regulations,” she said.

Clarke did not mention requirements such as the need to get a court order or for the enforcement of restrictions to be determined “on a case by case basis”.

But this doesn’t mean that the draft regulations are perfect. The experts we spoke to had several criticisms. What are the issues?

Draft ‘poorly written’ and seems to conflict with previous regulations

The draft does not explicitly mention that existing requirements like court orders would be required to enforce mandatory action. “This means the amendment is contradictory to the existing regulation,” London said.

The draft also doesn’t specify when the regulations would be enforced, or how they would apply to Covid-19 as the pandemic comes to an end.

“Technically, once enforced, it would be permanent or until the regulations are further amended,” London said.

Kruger told Africa Check that the draft was “unclear” about the process required for a person to be vaccinated. The phrase in the draft that prohibits people from refusing prophylaxis might be interpreted as grounds for mandatory vaccination, she said, but the draft “seems like a poor vehicle for a vaccine mandate”.

This was true of other aspects of the regulations, like quarantine. London said that according to the 2017 regulations, requirements like quarantine or isolation should be dropped “once someone is no longer posing a threat to public health”.

“Given the limited period of infectiousness of Covid-19, obtaining a court order might take longer than is practical to enforce a quarantine.”

Several prominent scientists have detailed the weaknesses in the proposed rules. You can read their analysis here.

Conclusion: Proposed regulations flawed, but would not override existing requirements

So, do the proposed regulations make mandatory vaccination, medical treatment and quarantine possible? According to experts, this would be difficult to enforce.

Any of the measures would require a case-by-case evaluation followed by a court order. But this is not immediately clear when the proposed regulations are read on their own.

Experts have taken issue with other aspects of the proposed regulations, such as their poor wording and inconsistencies. Ambiguous rules, particularly for health and Covid-19, can harm public trust and provide fertile ground for misinformation.

Add new comment