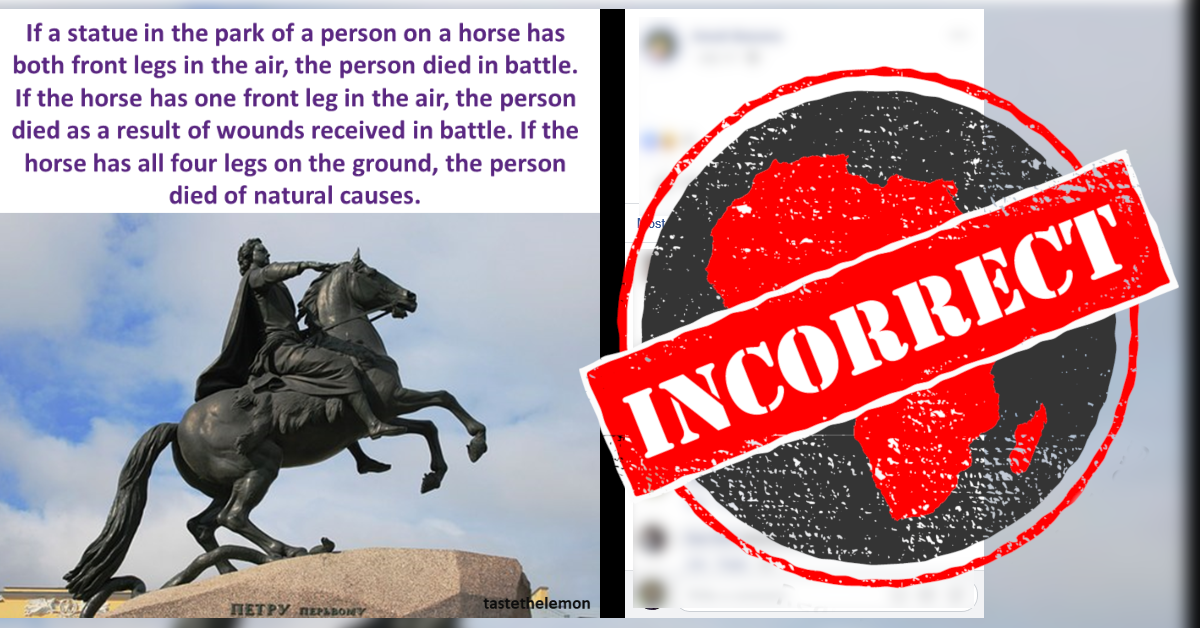

A meme shared on Facebook in South Africa shows a statue of a man on a rearing horse.

The text reads: “If a statue in the park of a person on a horse has both front legs in the air, the person died in battle. If the horse has one front leg in the air, the person died as a result of wounds received in battle. If the horse has all four legs on the ground, the person died of natural causes.”

The statue is of Peter the Great, a tsar who ruled Russia from 1682 until his death in 1725.

The horse in the statue has both front legs raised, so the if the meme is correct Peter the Great must have died in battle. But the tsar actually died of gangrene.

Fact-checking organisation Politifact debunked the claim in 2018. It does admit that most of the statues with horses at Gettysburg National Military Park in the US have this pattern. But the statue of Confederate general James Longstreet, whose horse has one foreleg raised, is an exception – he died at home days short of his 83rd birthday.

Reference site Thought Co says “there is no tradition of indicating on a statue how the individual died”.

“There is no established tradition of doing this in Europe, although the myth is widespread there.” It’s unclear where or when the myth began.

The Useless Info Junkie website points to the book From Marcus Aurelius to Kim Jong-il: The story of equestrian statues throughout the ages by Kees van Tilburg.

When the site asked Van Tilburg about the myth, he quoted from his book:

“A nonsense story coming up from time to time is that a statue contains a code whereby the rider’s fate can be determined by noting how many hooves the horse has raised. For example one hoof raised indicates wounded in battle, two raised hooves death in battle. Needless to say, even if such a code ever existed, almost no sculptor respected it.”

Fact-checking website Snopes says the supposed connection “is not ‘tradition’, but an attempt to create an interesting piece of information by finding patterns in randomness". – Taryn Willows

The text reads: “If a statue in the park of a person on a horse has both front legs in the air, the person died in battle. If the horse has one front leg in the air, the person died as a result of wounds received in battle. If the horse has all four legs on the ground, the person died of natural causes.”

Meme’s photo disproves it

The statue is of Peter the Great, a tsar who ruled Russia from 1682 until his death in 1725.

The horse in the statue has both front legs raised, so the if the meme is correct Peter the Great must have died in battle. But the tsar actually died of gangrene.

No established tradition

Fact-checking organisation Politifact debunked the claim in 2018. It does admit that most of the statues with horses at Gettysburg National Military Park in the US have this pattern. But the statue of Confederate general James Longstreet, whose horse has one foreleg raised, is an exception – he died at home days short of his 83rd birthday.

Reference site Thought Co says “there is no tradition of indicating on a statue how the individual died”.

“There is no established tradition of doing this in Europe, although the myth is widespread there.” It’s unclear where or when the myth began.

‘A nonsense story’

The Useless Info Junkie website points to the book From Marcus Aurelius to Kim Jong-il: The story of equestrian statues throughout the ages by Kees van Tilburg.

When the site asked Van Tilburg about the myth, he quoted from his book:

“A nonsense story coming up from time to time is that a statue contains a code whereby the rider’s fate can be determined by noting how many hooves the horse has raised. For example one hoof raised indicates wounded in battle, two raised hooves death in battle. Needless to say, even if such a code ever existed, almost no sculptor respected it.”

Attempt to create interesting information

Fact-checking website Snopes says the supposed connection “is not ‘tradition’, but an attempt to create an interesting piece of information by finding patterns in randomness". – Taryn Willows

Republish our content for free

For publishers: what to do if your post is rated false

A fact-checker has rated your Facebook or Instagram post as “false”, “altered”, “partly false” or “missing context”. This could have serious consequences. What do you do?

Click on our guide for the steps you should follow.

Publishers guideAfrica Check teams up with Facebook

Africa Check is a partner in Meta's third-party fact-checking programme to help stop the spread of false information on social media.

The content we rate as “false” will be downgraded on Facebook and Instagram. This means fewer people will see it.

You can also help identify false information on Facebook. This guide explains how.

Add new comment