The massive movements of people, fueled by the ongoing Syrian refugee crisis, has put migration at the top of the global human rights agenda. According to a recent United Nations report, international migrants – those living in countries other than where they were born – reached 244 million in 2015, a 41% increase from 2000. Those numbers include 20-million refugees – broadly defined as those fleeing conflict or persecution from their country of origin – the highest level of refugees the world has seen since World War II.

It is these movements which have caused the United Nations to call its first ever high level summit on refugees and migrants, which will be held this September in New York.

But to begin to understand the root causes and underlying issues as well as possible solutions, it is important to first have a deeper understanding of the basic terms around migration. It is these definitions which determine how migration issues are understood globally, and how people may be categorised and treated by the international community as well as in the countries which they move to.

The United Nations report found that 20 countries host 67% of the international migrant population, with the United States topping the list, followed by Germany and the Russian Federation. The only African country on that list was South Africa.

According to Professor Loren Landau, the South African Research Chair in Mobility and the Politics of Difference at the African Centre for Migration and Society at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa receives migrants who are seeking work, protection or hoping to proceed to other countries.

“We often speak about three motivations: passage, profit and protection. For some it is a stepping stone to get elsewhere, for others it is a place to work or prepare for life; that is, to study and learn skills. Still others hope to escape conflict or persecution. Often it is some combination,” he says.

Who is a migrant?

The International Organisation for Migration defines a migrant as any person who has moved across an international border away from their habitual place of residence,whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary, regardless of the person’s legal status the reason for the move, or their length of stay.

Dr Sally Peberdy, a senior researcher at the Gauteng City-Region Observatory who has conducted several studies on migration, explained a migrant can be someone who has “changed cities, provinces, countries or continents. It can be someone gone for good or away only for a season.”

Migration where “an element of coercion exists, including threats to life and livelihood, whether arising from natural or man-made causes,” is known as forced migration.

According to the International Organisation for Migration IOM, migration can also be internal, within a country. In South Africa, domestic migrants include people who have two homes, according to Landau. Such migrants are referred to as circular migrants and Landau cites mineworkers as examples.

Are refugees migrants?

The United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) has been campaigning for refugees to have better access to legal protection. In July 2016 the agency published an article calling for the public to differentiate refugees from migrants following heated discussions about the definitions in the aftermath of the Syrian refugee crisis. It argued that since refugees are forced to move, they are not migrants. But this distinction seems to contradict International Organisation for Migration’s definition of a migrant.

“The IOM’s definition matches a more common sense or sociological one: refugees and internally displaced persons are a sub-type of migrants generally,” said Landau.

Maurice Smithers, project manager for a coalition of several civil organisations in South Africa called the People’s Coalition Against Xenophobia (PCAX), agreed refugees fall under the broad category of migrants but said there is a need to clarify when using the terms.

“It is very important there is clarity in people’s minds. Are you talking about a person who just comes into the country looking economic opportunities or someone who needs protection?” said Smithers.

He said countries can come up with their own regulations on migrants but the countries that signed United Nations protocols, such as South Africa, are bound by international resolutions to protect refugees.

How does an asylum-seeker differ from a refugee?

South Africa’s department of home affairs defines an asylum seeker “as a person who has fled his or her country of origin and is seeking recognition and protection as a refugee in South Africa, and whose application is still under consideration.”

The department states that if the application is denied, the person must leave the country or risk deportation.

The department defines a refugee as “a person who has been granted asylum status and protection in terms of the section 24 of Refugee Act Number 130 of 1998”, but a new Amendment Bill has recently been tabled which may change the terms of this Act.

“Asylum (refugee status) is granted on an individual basis, even though some countries – for example, Somalia – are seen as refugee producing,” said Peberdy, adding “in South Africa a refugee has the same rights as a South African except the right to vote.”

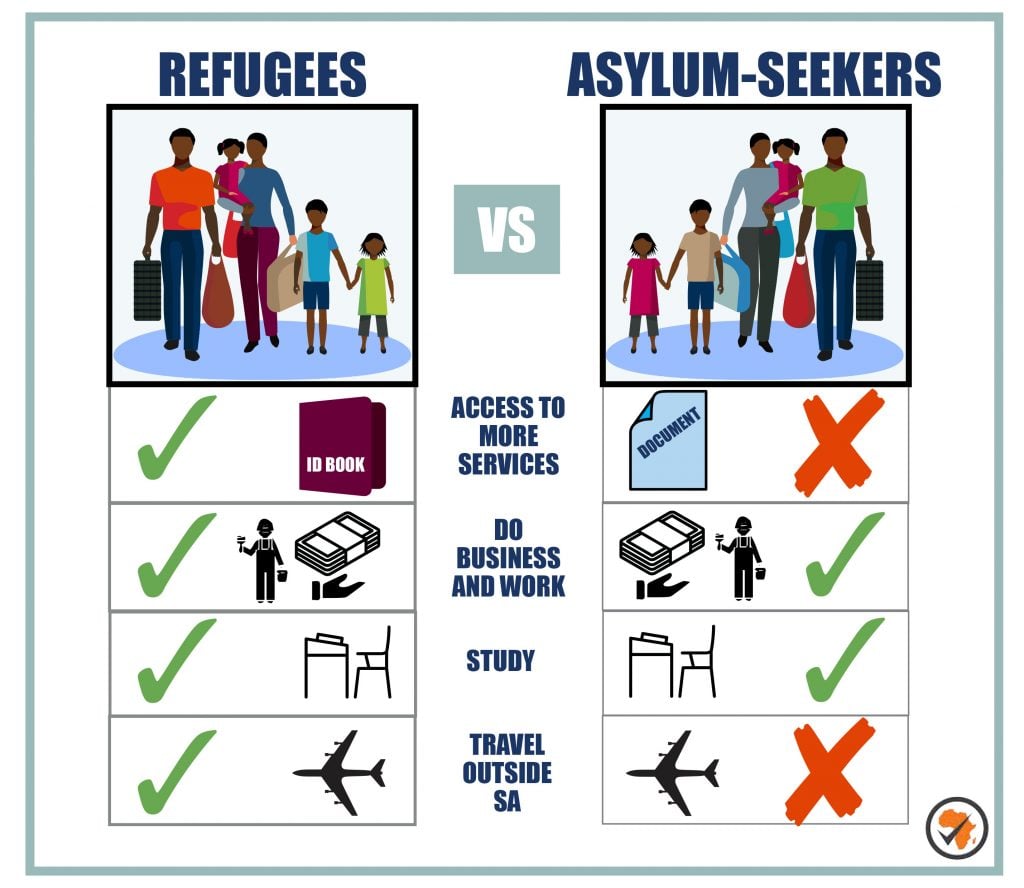

Refugees receive a maroon ID book while asylum-seekers use an A4 piece of paper, which most people do not recognise, according to David Cote, programme manager for the Strategic Litigation Unit at Lawyers for Human Rights. The ID book gives refugees access to more services than asylum-seekers, but both refugees and asylum-seekers can legally work, study and do business.

While refugees have permission to travel, asylum-seekers must remain in the country until the adjudication process is completed, Cote said. The adjudication process is supposed to be completed within 180 days but according to Cote it can take years.

Countries are free to define refugees in their own ways but South Africa is a signatory of the 1951 United Nations Convention and has adopted the United Nation’s definition. Landau notes that South Africa also has signed the slightly more expansive African Union convention on refugees.

“In practice South Africa is more restrictive than either of those definitions,” Landau said, adding that the South African government has been unwilling to grant asylum to many people who have consistently met the criteria for refugee status. In a review done by the ACMS and Lawyers for Human Rights, researchers found instances where applications from certain groups, like women who have been targeted for politicised forms of sexual violence, were rejected.

“In some cases these and other rejections are simply because the decision was rushed or the status determination officer was ignorant of the law,” said Landau.

Unlike other countries where refugees stay in camps, South Africa does not have an encampment policy. Asylum seekers and refugees stay in communities throughout the country.

How does a migrant differ from a visitor?

A study conducted under the Southern African Migration Programme in 2001 found some migrants enter South Africa as visitors even when their intention is to work. So how does a visitor differ from a migrant?

“The border is blurry, but we usually consider a migrant as someone hoping to establish themselves, however temporarily, in a new site. This can be through marriage, studying, work, or residence like retirement. A visitor may be there to trade, but not to live,” said Landau.

Tourists, people visiting family or friends, people attending conferences and people coming for short trips for business are visitors and not migrants.

All migrants are required by law to obtain necessary visas from the South African embassies in their countries of residence before moving. Visas are also required for visitors but the office which is mandated to manage international migration, the department of home affairs, exempts citizens from a number of countries. The exemptions vary from periods of 30 to 120 days.

What is the difference between a documented and an undocumented migrant?

All migrants holding valid residence visas or permits are referred to as documented migrants. The department of home affairs provides different types of temporary residence visas. After fulfilling certain requirements, qualifying migrants can also apply for permanent residence.

According to section 25 of the Immigration Act of 2002, permanent residents enjoy the same rights as South Africans, except rights restricted to citizens by the Constitution. For instance, a permanent resident cannot vote and can be deported if they commit a crime as scheduled in the Immigration Act, explains Peberdy. Permanent residents can become citizens if they meet the criteria in the Citizenship Act of 1995.

Migrants that do not have valid residence visas are referred to as undocumented, irregular, illegal migrants or even illegal aliens. Landau describes the terms as technical and highly politicised.

“Irregular is my preferred term for those who are not authorised,” Landau says, “because while an action may be illegal, a person is not.”.

According to Peberdy, irregular migrants include people who have “entered the country without documents, without the correct documents for the purpose of their visit, who have overstayed their permit or who have entered into activities not covered by their permit.”

Decolonising South Africa’s migration policies

The Green Paper on International Immigration, published in June 2016, makes prominent reference to historical colonial systems of labour migration, particularly in the SADC region, that predated 1994. The paper states that South Africa has been the African continent’s main destination for migrant labour since the discovery of mineral resources in the late 19th century.

In the past, South Africa, had special arrangements with mine workers from countries like Botswana, Mozambique and Swaziland. According to Peberdy, contract workers on the mines and commercial agriculture workers from other countries are given different permits under the Immigration Act, which are governed by longstanding bilateral agreements.

For instance, according to section 21 of the Immigration Act 2002, employers can obtain a corporate permit which allows them to employ a specific number of foreigners for a specified period.

Peberdy says, generally, the difference in those special agreements is that is when mine workers are employed under corporate and/or treaty permits, the mine worker is not allowed to be joined by his family, nor are they allowed to claim permanent residence even if they have worked in South Africa for five years and meet other requirements.

However, she said that in 1995 the South African government gave mineworkers who had worked in South Africa for 10 years or more the opportunity to apply for permanent residence.

“There are also border agreements with neighbouring states allowing people living within a specified distance of the border, and even specific parts of the border, permission to cross without going through border posts to a specified distance from the border. This is to deal with communities that are separated by imposed borders,” she says.

Peberdy points out that with the exception of the above, it is virtually impossible for unskilled, semi-skilled or artisanal workers to gain legal entry to South Africa.

South Africa also has two special permit programmes, for nationals of Zimbabwe (the Zimbabwean Special Dispensation Permit) and Lesotho (the Lesotho Special Permit).

Edited by Tanya Pampalone

Key legislation and resources

|

Additional Reading

Do 5 million immigrants live in S. Africa? The New York Times inflates number

Are foreigners stealing jobs in South Africa?

The new special dispensation permit and what it means for Zimbabweans in SA

How many Zimbabweans live in South Africa? The numbers are unreliable

Is South Africa the largest recipient of asylum-seekers worldwide? The numbers don’t add up

Add new comment