Are white Afrikaners really being killed “like flies”? Is a white South African farmer being “slaughtered every five days?” Would the number of whites “killed in SA in black on white violence” fill one of the country’s largest football stadiums?

These are some of the claims made recently by Steve Hofmeyr, one of South Africa’s most popular, and controversial, Afrikaans singers and performers. In a post on his blog and Facebook page titled “My tribe is dying”, Hofmeyr made several sweeping statements about South Africa’s murder rate and the quality of life of white Afrikaans-speaking South Africans.

Within a day of it being posted, Hofmeyr’s blog entry and a pie chart that he used to support some of his claims were “liked” by more than 2,000 Facebook users. A similar number also shared the post on their Facebook pages.

The Facebook entry was subsequently removed but later reposted without the pie chart. By way of explanation Hofmeyr stated: “The facts are good but they shouldnt be in a pie-chart. Im removing the pic. It will be replaced with the real PIE.” On his Facebook page Hofmeyr explained the issue with the pie chart was not with the statistics, rather: “It should be separate charts (pre&post Apartheid).”

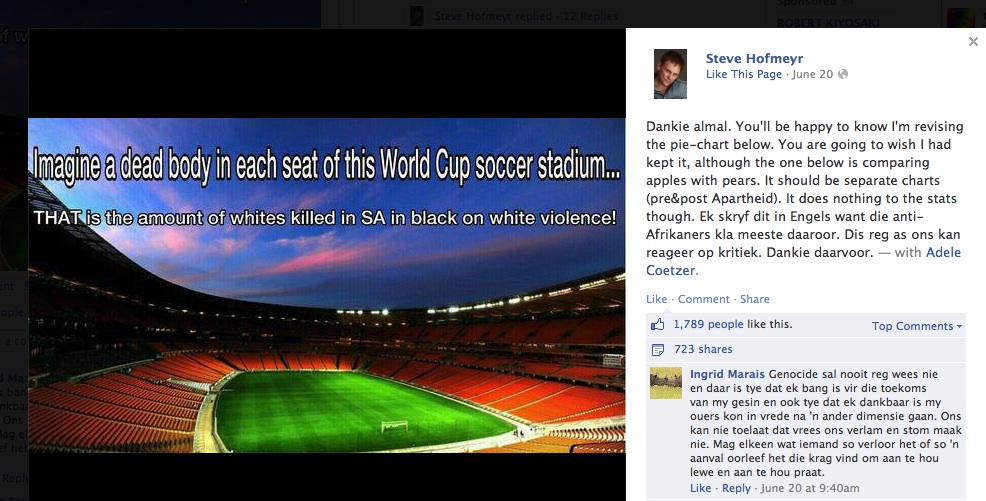

At the same time, Hofmeyr posted an image of the interior of a “World Cup soccer stadium” - which appears to be Johannesburg’s Soccer City - together with a statement that the “amount of whites killed in SA in black on white violence” would produce a body count capable of filling the stadium’s seats.

'A lot of bodies to lose in stats'

- “Old SA averaged 7039 murders/year from 1950. New SA averaged 24206 (SAP) or 47882 (Interpol). Sorry Columbia (sic). We still champs.”

- “When SAP claimed 26000 murders in 96, Interpol counted 54000. A lot of bodies to lose in stats.”

- “There is a discrepancy of 10 000 murders per year between government and MRC figures!”

Several readers asked Africa Check to investigate the accuracy of Hofmeyr’s various claims, among them that:

- Whites are being murdered at a rate faster than any previous period in South Africa’s history.

- A white farmer is murdered every five days.

- During apartheid, black-on-black violence was responsible for the majority of black homicides, with only a fractional percentage of black murders due to government forces.

- “Whites killed by blacks since apartheid 77.3%”. This is unclear as Hofmeyr has not indicated what factor the percentage is of however Africa Check assumes Hofmeyr is stating 77.3% of all white homicides (since 1994) have been perpetrated by blacks.

- The number of whites killed by blacks in South Africa is equivalent to, or more than, the number of seats at Soccer City stadium, which has a maximum seating capacity of 94,736.

- There are significant discrepancies between murders reported by the South African Police Service and other agencies and that these discrepancies have been used to hide or obscure the “truth” about murder in South Africa.

Where does Hofmeyr get his information?

On various white right-wing sites, reference is made to a "Vusile Tshabalala" who supposedly wrote an article in 2001 about the "killing fields" of post-apartheid South Africa. Invariably the sites describe Tshabalala as a "journalist" and then, for emphasis, as a "black journalist". No indication is given of where Tshabalala worked, nor does he appear to have written any other articles.

Hofmeyr’s other claims appear to stem from a 2003 paper titled, “Murder in South Africa: a comparison of past and present”. It was written by Rob McCafferty, then a communications director for the conservative Cape Town-based lobby group, United Christian Action.

McCafferty’s paper, published at the peak of crime levels in South Africa, appeared to offer a comprehensive survey of crime literature and subsequent analysis of crime data and trends over a period of more than five decades. There are, however, several significant flaws in the presentation and interpretation of data, some of which McCafferty acknowledged himself.

There are no 'average' murders

McCafferty’s paper presented a graph based on figures sourced directly from “annual police reports and CSS: Statistics of Offence annual reports” showing the total number of murders reported to the police between 1950 and 2000.

McCafferty’s paper presented a graph based on figures sourced directly from “annual police reports and CSS: Statistics of Offence annual reports” showing the total number of murders reported to the police between 1950 and 2000.McCafferty conceded in his paper that “factors such as population growth and differentials in time periods...would make it unfair to compare this data” and pointed out that it was “not logically sound to do such comparisons”.

But McCafferty proceeded to do just that and aggregated 44 years of murder numbers (309,583 recorded murders from 1950 to 1993) to reach an “average” of 7,036 murders a year under apartheid.

He then contrasted that figure with his own aggregation of post-1994 Interpol statistics, from which he determined an annual average of 47,882 murders.

This appears to make a case for a shocking increase in homicides in the post-apartheid era. But, as we explain below, the Interpol murder statistics McCafferty used are widely regarded as inaccurate. And McCafferty’s “average” murder numbers show a very different picture when plotted against South Africa’s population figures.

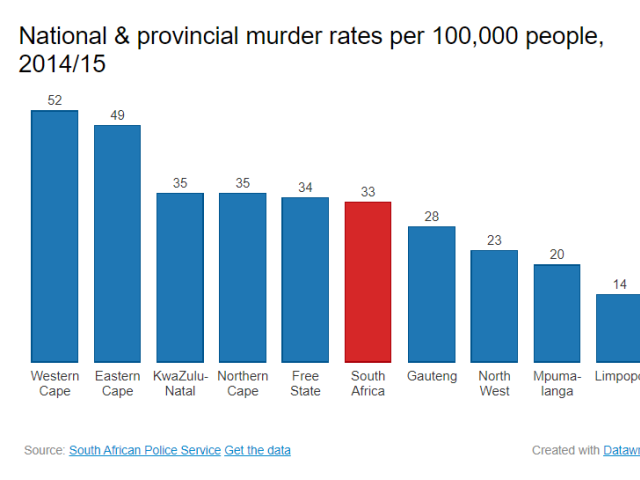

Murder and other crime statistics are commonly expressed by statisticians, crime analysts and researchers as a ratio per 100,000 of the population rather than in raw numbers. McCafferty’s failure to have done so indicates exactly why this is preferred practise.

According to McCafferty’s graph, less than 2,500 murders were reported to the police in 1951. The census results of that year indicate that the total population of South Africa at the time was 12,671,452. The “murder ratio” therefore works out at 19.73 murders for every 100,000 people.

By 1970, the total number of reported murders appeared to be approaching 7,000. With a population of about 21,7-million, this would equate to a murder ratio of 32.12 per 100,000.

McCafferty’s graph showed that the number of homicides increased steadily from 1950. What McCafferty had not taken into account was that South Africa’s population had also steadily increased.

By 1994, SA’s murder numbers, according to McCafferty, had reached 25,000 a year. With a population of just under 40-million, this translated to a murder ratio of a 62.5. South Africa's murder rate for all races peaked in the period during and following the transition to democracy.

However, in a paper published by the Medical Research Council, crime analyst and author Antony Altbeker found that by 2003/4 the rate had fallen to less than 43 murders per 100,000. The murder rate has continued to decline since then, dropping to 30.9 for 2011/12 according to the South African Police Service Crime Statistics Overview. Significantly, given Hofmeyr’s claims, it is lower than the murder rate documented in 1970 under apartheid.

All the independent security and research experts we consulted for this report agreed that current murder figures provided by the South Africa Police Service (SAPS) should be considered accurate.

The trouble with apartheid-era data

Both Altbeker and Mark Shaw, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies who has worked extensively with apartheid-era crime data, told Africa Check that official police figures during apartheid were not an accurate representation of national homicide rates.

Both Altbeker and Mark Shaw, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies who has worked extensively with apartheid-era crime data, told Africa Check that official police figures during apartheid were not an accurate representation of national homicide rates.Crime reports from the Bantustans - the nominally independent black “homelands“ established under the auspices of the apartheid state - were not included in South Africa’s national figures. In addition, according to Shaw, “a proportion of homicide cases among Africans were not reported or recorded” owing to the absence or lower levels of policing in the townships and rural areas.

Therefore it is probable that while white homicides during apartheid were accurately documented by the state, the number of black homicides was understated in official reports. For this reason, the “blacks killed” portions of Hofmeyr’s chart must be discounted; the data is simply not reliable enough to make any accurate findings – and the role of apartheid in creating or contributing to violence and murder in black communities is difficult to isolate.

Since 1990, race has not been listed as a category in official death records. This deliberate omission may have been intended to avoid exactly the kind of issue raised by Hofmeyr’s claims; the interpretation of raw data by non-experts to support some form of race-based conspiracy theory. In reality, however, the absence of such information has effectively perpetuated a race-crime mythology in South Africa.

It is, however, possible to gauge trends in white homicide based on older data. A 2004 report published in the SA Crime Quarterly compares homicide rates across all races from 1937 to 2003. Based on this, it is clear that homicide rates for all races increased over this period (although they fell somewhat from 2003 onward). However, the increase in the white homicide rate began in the late 1970s and has remained markedly less than the increase in murder rates for all other race groups.

Murder by numbers

A central thread of Hofmeyr’s claims relates to apparent discrepancies in South African murder statistics. Hofmeyr cites figures that appeared in McCafferty’s report which stated that “[w]hile police crime statistics show there were 21,683 murders in 2000, the [Medical Research Council] puts the figure at 32,482". McCaffrey also stated that ”while the SAPS claims there were 26,883 murders in 1995/96, Interpol claims there were 54,298”.

A central thread of Hofmeyr’s claims relates to apparent discrepancies in South African murder statistics. Hofmeyr cites figures that appeared in McCafferty’s report which stated that “[w]hile police crime statistics show there were 21,683 murders in 2000, the [Medical Research Council] puts the figure at 32,482". McCaffrey also stated that ”while the SAPS claims there were 26,883 murders in 1995/96, Interpol claims there were 54,298”.In its report at the time, the MRC said it “notes discrepancies in the statistics concerning road traffic accident deaths and homicides which needs further investigation”. A revision of the 2000 data was published in 2006, in which the total number of deaths was revised downwards, from 550,000 to 520,000, and the “number of injury deaths” [which include homicide and traffic accidents] was “revised down by about 10,000”.

Based on this updated information, it was stated that “[o]f the estimated 59,935 injury deaths in 2000, 46% (27,563) were homicides”. That still leaves a discrepancy of nearly 6,000 deaths.

Altbeker dealt with this specific issue in great detail in his report on murder and robbery in South Africa, in which he argued that “the MRC’s figures cannot be reliably used to refute the numbers presented by SAPS”. In short, he found that the data used to compile the MRC’s estimates had been incomplete or flawed and had yielded an inaccurate and overstated picture.

The “murder gap” between Interpol and SAPS numbers is easier to explain. Altbeker told Africa Check that Interpol combined both murder and attempted murder figures for South Africa, resulting in inflated numbers. This is confirmed by the 1999 Global Report on Crime and Justice published by the United Nations Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention. Altbeker wrote extensively about the challenges with international crime data collection and comparison in a separate paper.

Both McCafferty and Hofmeyr’s claims about murder number discrepancies must therefore be dismissed.

White death in a time of democracy

“Whites are far less likely to be murdered than their black or coloured counterparts,” Lizette Lancaster, who manages the Institute for Security Studies crime and justice hub, told Africa Check. This is supported by an analysis of a national sample of 1,378 murder dockets conducted by police in 2009. In 86.9% of the cases, the victims were Africans. Whites accounted for 1.8% of the cases (although whites make up 8.85% of the population).

According to Lancaster official police statistics show that between April 1994 and March 2012 a total of 361 015 people were murdered in South Africa. Applying the 1.8% figure, it would mean that roughly 6,498 whites have been murdered since April 1994.

Even if there were some variation on the 1.8% figure, the number of white murder victims would still fail to come anywhere close to filling a soccer stadium. The fact is that whites are less likely to be murdered than any other race in South Africa. The current murder rate of white South Africans is also equivalent to, or lower than, murder rates for whites recorded between 1979 and 1991.

According to the 2011/12 SAPS annual report, Lancaster said,“only about 16% of murders occurred during the commission of another crime, mainly aggravated robbery. About 65% of murders started off as assaults due to interpersonal arguments and fuelled by alcohol and/or drugs, result[ing] in a murder”. The vast majority of murders are, she said,“social fabric crimes often perpetrated by friends or loved ones”.

The 2012 Victims of Crime Survey confirmed this assertion, stating that 16.1% of victims were “murdered by unknown people from outside their residential area” with an additional 10.9% of “murders ... committed by known perpetrators outside [the victims’] residential area”, and the balance of homicides committed by community members, spouses and friends or acquaintances.

Even if the proportion of “outsider” crime was doubled for white homicide victims, this would still fall drastically short of the “77.3%” of white murders that Hofmeyr appears to claim are at the hands of black perpetrators.

Farm attacks

The interpretation of data on “farm attacks” is problematic as it relies on old police data and current, self-reported data collected and submitted by the Transvaal Agricultural Union of South Africa (TAUSA).

The interpretation of data on “farm attacks” is problematic as it relies on old police data and current, self-reported data collected and submitted by the Transvaal Agricultural Union of South Africa (TAUSA).TAUSA figures for the 22 years between 1990 and 2012 state that 1,544 people were killed in farm attacks, an average of about 70 a year or one every 5.2 days. A report by trade union Solidarity, issued in 2012, found that 88 farmers were murdered in the 2006 to 2007 financial year.

So was Hofmeyr correct in claiming that “a white farmer is slaughtered every five days”?

According to a 2003 police committee of inquiry into farm attacks, cited by Solidarity, 38.4% of farm attack victims were described as being black, coloured or Asian. TAUSA’s figures suggest that 208 (or 13.5%) of those murdered in farm attacks between 1990 and 2012 were black.

Hofmeyr’s statement that a white farmer is murdered every five days is therefore also incorrect. The claim would only be true if he included all farm attack victims of all races.

Conclusion: Hofmeyr's claims are grossly incorrect

Hofmeyr’s claims are incorrect and grossly exaggerated the level of killings.

South Africa certainly has one of the highest crime rates in the world and one that is characterised by a particularly high rate of violent crime. This is not an area where degrees of comparison offer any form of comfort. South Africans are affected daily by crime.

South Africa remains gripped by its fear of crime. In the 2012 Victims of Crime Survey, about 35% of households believed that crime had increased since the previous period.

Public figures like Hofmeyr, who disseminate grossly misleading information about crime patterns, only serve to contribute to this underlying fear. In addition, such misinformation creates or entrenches existing racial divisions and perpetuates an unfounded fear and hatred of other races.

Edited by Julian Rademeyer

Add new comment