The Jo'burger who went up a tree and came down to a forest

There’s a difference between fact checking and myth-busting.

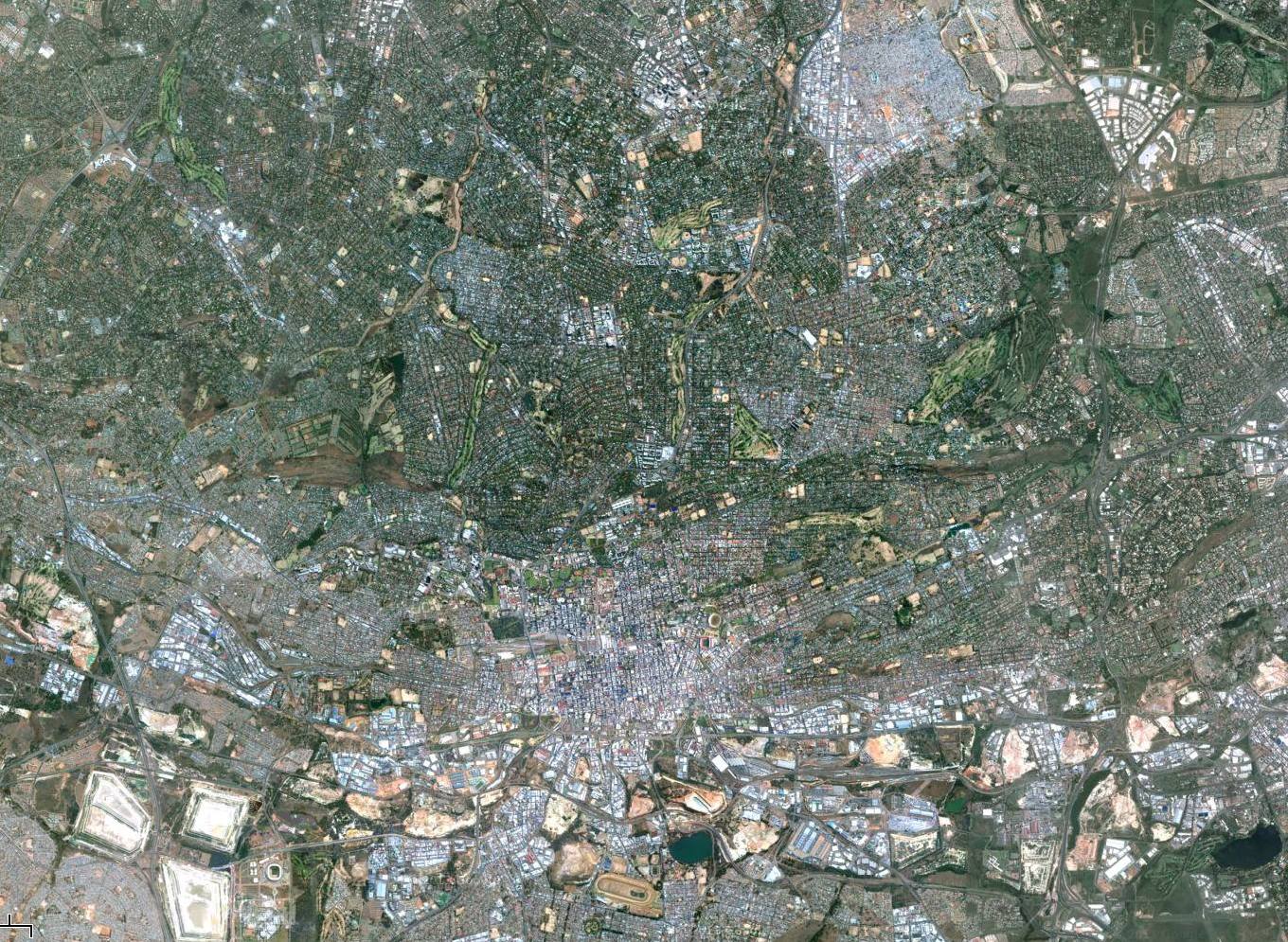

There’s a difference between fact checking and myth-busting.When Africa Check posted an article last week, stating that Johannesburg’s claim to being the “world’s largest man-made forest” was a myth, I took issue with the reporting – and not just out of a skewed sense of Job’urg patriotism (although there is that). I wasn’t satisfied with the way the facts were presented. So I decided to do a little checking of my own.

What Africa Check established was (my thoughts):

1. Jo’burg is not, actually, a forest. Well, yes. And no.

2. There are much larger man-made forests. Duh. Also: hello, Captain Obvious. I will try to explain why this is important in less puerile terms.

3. Finally, the report stated there were “no credible rankings for the largest man-made forest in the world or the largest urban forest or even the most forested city”. This is also not entirely correct.

Trees are really hard to count

To start off, I wanted some degree of comparison – what makes a really, really big forest (any kind of forest). So I set off looking for information about the biggest one I could think of, the Amazon Rainforest.

As it turns out, trees are really hard to count. They never return their census forms, and if one of them falls and nobody’s there to hear it… well, you get the picture.

I hit my first obstacle: unless I was prepared to rely on WikiAnswers, I couldn’t get any clear (methodical, accurate) idea of actual tree numbers in the Amazon.

Brazil recently announced plans for a National Forest Inventory project that would attempt to do exactly this: count the number of trees in the Amazon. It’s estimated it will take over four years, with 20 000 sample points at 20-kilometre intervals.

To save waiting 48 months, I decided I’d try to create an estimate by taking the average number of trees per hectare and then multiplying that by the total area of the rainforest.

Even this proved a challenge. The New York Times cited 20-60 trees an acre (or 148 trees per hectare). The Amazon environmental and educational ACEER Foundation said that, in some parts of the Amazon, as many as 300 tree species (that’s species, not individual trees – the latter number would be equal to or higher) could be found in one acre [or 600/hectare]. But let’s settle for a conservative number: 150 trees per hectare. The Amazon Rainforest is 550 000 000 hectares. That’s 82 500 000 000 trees. Give or take. It’s quite a lot of trees.

Man-made forests get pretty darn big

Man-made forests get pretty darn big

The Africa Check article mentioned a massive Chinese forestation project, to plant a “great green wall” over 500 000 square kilometres – stating that, even though actual tree numbers were not available, it was a bigger “man-made forest” than Jo’burg could ever hope to be.

But you don’t have to look as far as China to find a man-made forest that’s bigger than Jo’burg’s reported 10-million trees.

The 60-year-old Usutu pine plantation in Swaziland covers an area of 52 000 hectares (literally a fraction of the Chinese scheme). Rather usefully, reports on Usutu include things like the number of “stems per hectare” – upwards of 1200 – which makes it easier to work out how many trees there are: 62 400 000 (if all hectares were planted simultaneously).

Also quite a lot more than Joburg. And one would suspect there are hundreds if not thousands of such timber plantations all over the world. Jo’burg’s own trees take their origins from exactly such ventures, to provide timber for the mines.

So, is Jo’burg the world’s largest man-made forest?

Absolutely not – but comparing it with commercial timber plantations (or programmes extending across vast swathes of country) seems to be guided by the letter(s) of the word rather than the spirit or intention of the phrase.

By any conventional definition, Jo’burg is also not a forest. But it is a city and it does have a rather large number of trees. And, as it turns out, there is both research on and a name for this.

I invented a word – neoforestation – to try and explain the bit I need to talk about next.

Africa Check’s article describes an “urban forest” as a “looser term” meaning “a densely-wooded [sic] urban area” – and quotes a nice person from City Parks saying Johannesburg was “probably ‘only one of the largest man-made urban forests in the world’”.

Urban forests are a big deal

Urban forests are a big deal

It’s important we understand what is meant by “urban forest” because, as it turns out, it’s not a loose term at all. As the balance of the world’s population has shifted from rural to urban areas, “urban forests” are a pretty big deal in arboreal terms.

The United States Department of Agriculture’s Forestry Service has an Urban Forestry Program (only one “m” because, America) and has even developed a computer-based UFORE (Urban Forests Effects) model to start quantifying urban forests.

North America – Canada and the United States – pioneered the term “urban forestry” [it was first used in 1965], and the discipline has spread or gained popularity in other regions.

In a paper on urban forestry in Europe, Danish author Cecil C. Konijnendijk (who has written several books on the topic) defines urban forests as “all forest and tree resources in (and close to) urban areas”, and offers the following:

“‘Forest’ within ‘urban forest’ thus has been given a different meaning than the traditional forest concept encompasses. By including small woods, parks and gardens with area size and/or canopy cover below thresholds for ‘forest’, as well as individual trees the traditional forest concept has been broadened considerably.”

So: Johannesburg is an urban forest. Hurrah.

Is Jozi the biggest urban forest in the world?

The next question, then, was: is it the biggest urban forest in the world? And by ‘biggest’ I meant the most number of trees rather than the largest geographical area. [There’s a further condition – Jo’burg is a man-made urban forest. But we’ll get to why that’s important, again, later].

Africa Check said there were no credible rankings for such forest sizes – which is true. This does not mean, however, there is no credible information available on which we can make some kind of reasonable comparison… It just takes a lot more digging, using a Google spade.

Because I’d now, correctly, defined Jo’burg as an urban forest I was finally (in theory) able to compare like with like – by finding out the tree populations of other large settlements or cities around the world, and seeing where Jo’burg stacked up.

I did this in a very scientific manner, by asking Google variations of “how many trees are there in <city name>” until I found a report that came from a reputable source.

Finding the wood among the trees

Finding the wood among the trees

According to Africa Check, New York City had somewhere in the region of 5,2-million trees (and growing). So we were safe there. But that didn’t mean I could rule out the rest of the United States. Fortunately, the USDA Forestry Services had kindly compiled an entire report on urban forestry, and stated that urban tree populations ranged from 1,2-million (Boston) to a very worrying 9,4-million trees in Atlanta. I completely ignored Canada, as one does, but we all know they have more trees than people anyway.

Their colleagues across the pond had equally handy figures for London (some 7-million trees, including 500 000 street trees). I had a brief panic when a blogger wrote Sheffield had 200-million trees – but a quick check revealed the figure to be closer to 2,5-million.

I looked to Europe – Berlin has 439 000 street trees; Amsterdam (anecdotally – I couldn’t find an official report) has around 400 000 and is regarded as one of the “most-treed” cities on the continent.

In the Antipodes, Australia’s capital, Canberra (also a former “treeless plain”, much like Jo’burg) boasted only 400 000 trees. New Zealand, which “is dominated by trees with 59% of the land covered by a combination of native and exotic forests and vegetation” has relatively small urban settlements and a forestry report noted most of the country’s forests were located a “substantial [distance] away from the main population centres”. So I could exclude those…

India provided a 2008 tree census measuring 1,9-million trees in Mumbai. Ahmedabad claimed 618 000 trees. A proposed tree census in Delhi (reported to be India’s third most-treed city) had suffered delays, and no information was available but – based on the other cities’ data – seemed unlikely to challenge Jo’burg’s primacy.

Southeast Asia, Central and West Africa excluded

Lack of resources and time prompted me to exclude settlements built in existing forests or rainforests or jungles – which would count out most of south-east Asia, and central and west Africa.

For the same reason it would exclude Rio de Janeiro’s Tijuca National Park (mentioned by Africa Check, and which I had to the good fortune to visit last year) – although Tijuca had been extensively re-forested (i.e. planted) by man.

For the purpose of further clarity on Tijuca, I even tried to work out how many trees might be in the park. In the absence of any other information I had to estimate this using the density of trees in the Amazon (Tijuca is in a sense an extension of this, although if I recall it is an Atlantic rainforest) and the size of the park – between 3300 and 3900 hectares. Which, at 150 trees per hectare, works out to less than 600 000 trees.

North America, South America, Europe, Africa, the subcontinent…

That left the lingering threat of Atlanta – which I was going to neutralise by noting that the city falls within an existing forest biome, and therefore not only did Jo’burg have marginal superiority by numbers it could also boast its trees were imposed by man and not nature – and the one country I’d been avoiding, because I was worried what I might find.

The Nanjing Issue

During my Google-ing I found two references stating that the city of Nanjing had planted 34 million trees since 1994. Except the first citation (in a UN report) was dated 1993 (pre-planting, and the reference could not be traced). A later (2000) reference – indicating 23 trees per city dweller, which would have worked out to an even more impressive 50,6-million trees – also could not be verified or traced.

Ordinarily I would accept a UN report as a good source, but to have an urban forest of between 30-million and 50-million trees seemed so inordinately massive, given all the other cities mentioned above, that I was troubled by my inability to find more data on it, more mentions or studies of the scale of this massive forest, and – on Google Earth – to find a visual representation of a city that is a third the [population] size of Jo’burg but boasted three or more times the number of trees… A 2008 study on Nanjing’s urban forest commented the city was chosen because it had “relatively good tree cover”, which would be a bit of an understatement if the above figures were even close to true. Further, the only recent news stories I could uncover about Nanjing’s trees were moves to protect trees in the city (again, not quite in line with the army of urban trees painted above).

Conclusion

Conclusion

My Spidey senses, for what they are worth, force me to reject the claims of 34 million trees in Nanjing, because I could find no evidence aside from untraceable citations (referencing is so important, kids).

Given that, and given all of the other cities listed and mentioned above, it appears that Johannesburg is the largest man-made urban forest in the world.

There is a personal and professional downside to this. Because it turns out Wikipedia had it right all along.

Nechama Brodie is a freelance journalist and the editor and co-author of The Joburg Book, which is published by Pan Macmillan and Sharp Sharp Media. She used to be a pretty good tree-climber too. Find her at nechamabrodie.com

Add new comment