The year 2014 was a “devastating” one for children in armed conflicts, according to the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef).

Worldwide, 230 million children lived in countries affected by armed conflicts; 15 million were caught up in violent conflicts in countries such as the Central African Republic (CAR) and South Sudan; hundreds were kidnapped; and tens of thousands were recruited or used by government forces and armed groups.

The recruitment and use of children by armed groups is one of “six grave violations” against children identified by the United Nations Security Council. Yet the practice is pervasive, despite various legal instruments that aim to protect the rights of children in conflict.

Who is a child soldier?

A child associated with a government force or armed group is “any person below 18 years of age who has been recruited or used by an armed force or armed group in any capacity, including but not limited to children, boys, and girls used as fighters, cooks, porters, messengers, spies or for sexual purposes”. This is according to the Paris Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups, an agreement reached at a 2007 conference on children in armed conflict hosted by the French government and Unicef.

Child soldiers are often forcibly conscripted through coercion, abduction and threat. Others voluntarily enlist in armed groups.

However, the office of the special representative of the UN secretary-general for children and armed conflict noted that “voluntary enlistment” is something of a misnomer. Children present themselves to join armed groups in “a desperate attempt to survive” and escape poverty and insecurity.

How many child soldiers are there?

Accurate figures pertaining to child soldiers around the world are difficult to come by. A child protection specialist at Unicef, Ibrahim Sesay, told Africa Check that a lack of access to territories under the control of armed groups and the difficulty of determining the age of children who do not have birth certificates hampers research.

However, Unicef does undertake assessments in states and communities affected by conflict.

“The number of children recruited and embedded within the command structures of armed forces or armed groups are based on estimates per geographic location,” Sesay said.

Information is drawn from various sources, including informants, armed forces and armed groups. Data is then aggregated and triangulated (confirmed by more than one method of data collection) to assess validity and consistency.

In 2007, Unicef estimated 250,000 children were active in armed forces across the world.

Unicef does not have current estimates of the total number of child soldiers around the world and in Africa. A breakdown will only be available once research is completed next year.

However, Sesay said their research points to “tens of thousands” child soldiers around the world, with 12,000 children currently used by armed forces and groups in South Sudan, and 10,000 recruited in the CAR in 2014.

What is being done to end the use of child soldiers?

Various international groups, such as Child Soldiers International, War Child and the International Rescue Committee, work to eliminate the use of child soldiers. This is done through research, monitoring, advocacy and policy development, or through grassroots work with former combatants.

The UN started monitoring and reporting on violations against children in armed conflict in 2005, when the Security Council mandated it. In accordance with this, the secretary-general provides an annual report on children in armed conflict, as well as country-specific reports.

The monitoring mechanism was put in place to ensure children are protected in line with international legal benchmarks. The most recent of these include the Optional Protocol on the Convention of the Rights of the Child and the Rome Statute.

The UN’s Optional Protocol on Children in Armed Conflict, which entered into force in 2002, obligates signatories to raise the age of voluntary recruitment from 15 years, and sets the benchmark for compulsory recruitment by states and participation in hostilities at 18 years. It also forbids non-state armed groups from recruiting or using children under the age of 18.

The Rome Statute, which created the International Criminal Court (ICC) and also entered into force in 2002, sets another benchmark by making it a war crime to conscript or enlist children under the age of 15, or have them participate in hostilities.

In December 2014, the former commander-in-chief of the Forces patriotiques pour la libération du Congo (FPLC) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) became the first person to be convicted of the crime by the ICC. Thomas Lubanga Dyilo was sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment.

The UN launched the Children, Not Soldiers campaign last year to end the recruitment and use of child soldiers in government forces by 2016. Countries of concern include the DRC, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan, as well as Afghanistan, Myanmar and Yemen.

How is Africa faring?

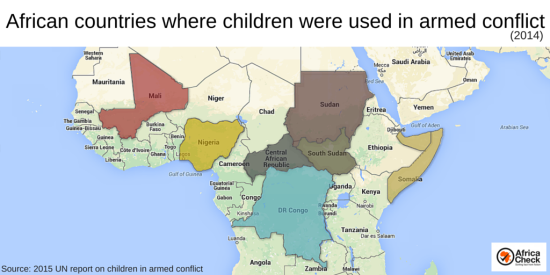

The UN secretary-general’s 2015 report on children in armed conflict listed 57 parties that recruited or used children in armed conflict last year. These included 29 parties in seven African countries:

- Boko Haram in Nigeria,

- Al-Shabaab in Somalia,

- the Lord’s Resistance Army, which is active in central African states such as the CAR, DRC and South Sudan,

- various rebel groups in the DRC, South Sudan, Sudan and Mali,

- the ex-Seleka and anti-Balaka in the CAR, and

- government forces from the DRC, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan.

Chad, a previous offender, was delisted from the report after it complied with all the measures set out in its action plan to end the recruitment and use of children.

The report stated that the DRC, Somalia and South Sudan had signed or recommitted to action plans to end violations against children. Sudan alone had yet to sign an action plan.

Add new comment