This article is more than 7 years old

Lindela Repatriation Centre was established by the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) in 1996 as a holding facility for foreigners awaiting deportation. It is not a refugee camp; South Africa has no refugee camps.

The only facility of its kind in South Africa, Lindela is located in Krugersdorp West about 40 kilometres outside of Johannesburg. It has facilities for up to 4,000 people, with separate areas for men and women. The management of Lindela is contracted out by the DHA to Bosasa, a private facilities management company. In the past few years Lindela has been featured in the news with allegations of bad treatment of foreigners, and human rights violations.

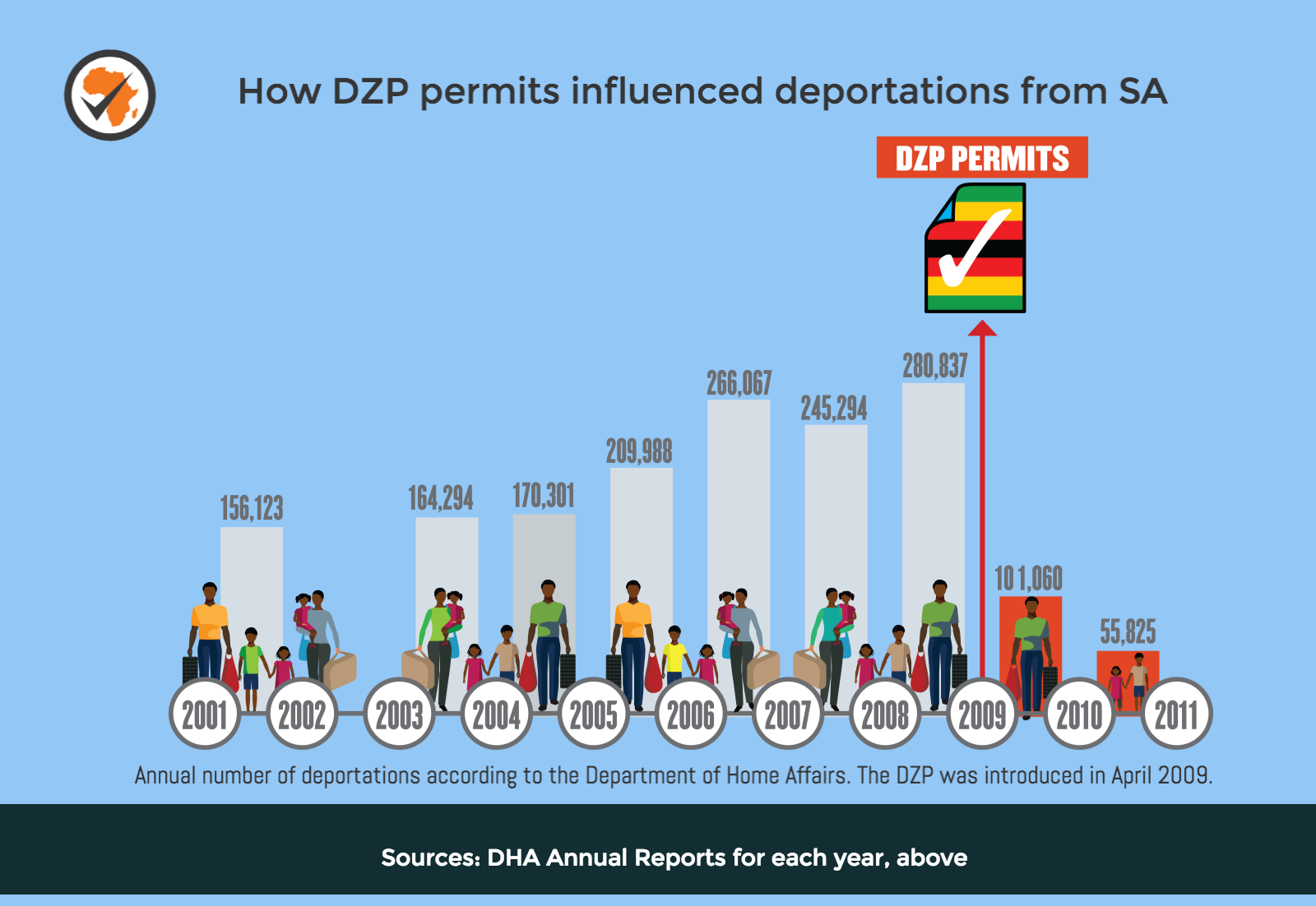

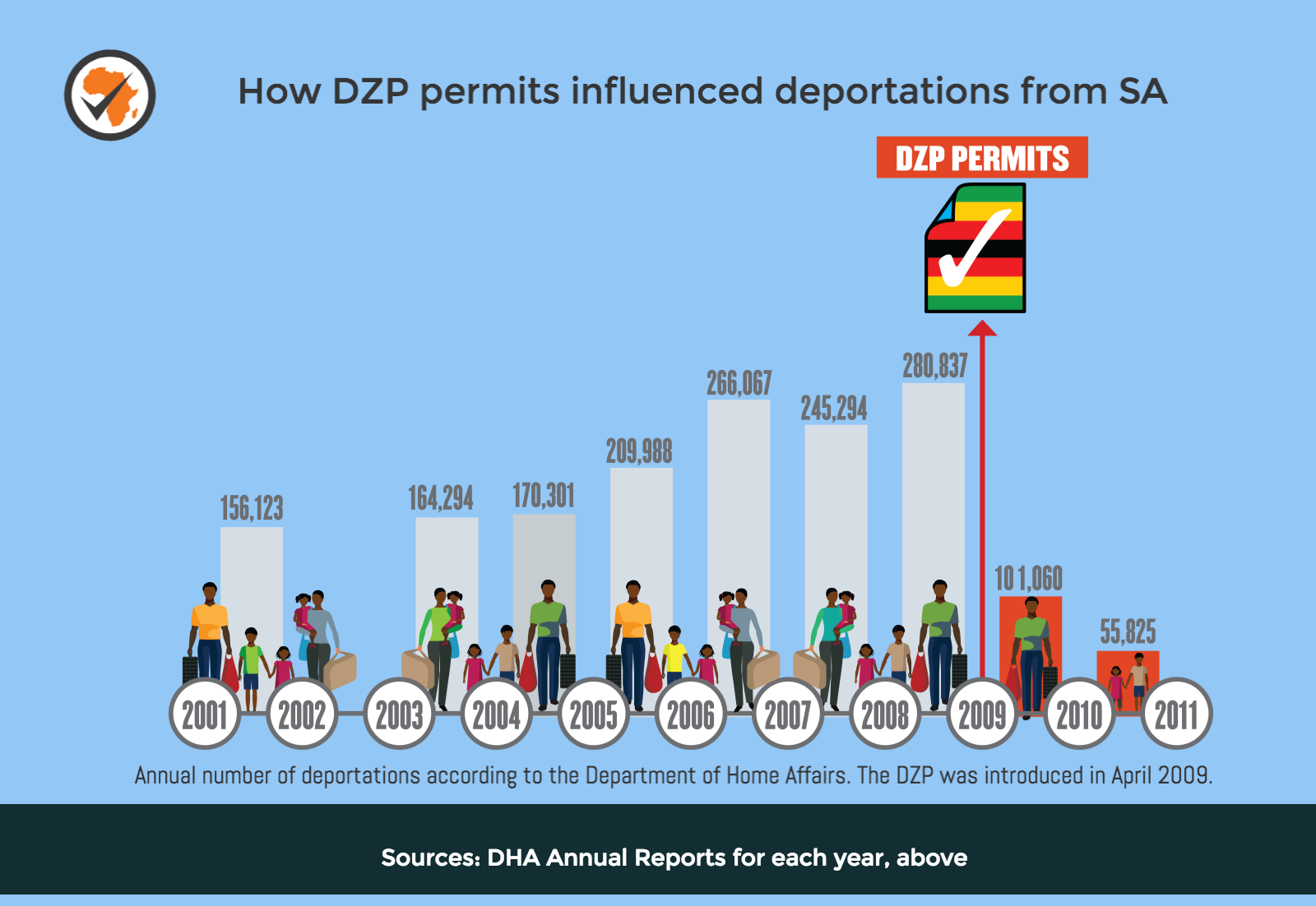

According to the DHA’s most recent annual report, during the 2014/15 financial year 54,169 people were deported from South Africa. This less than half the 131,907 people reported as being deported in the previous year, and lower still than the period prior to 2009, when deportation rates were regularly in excess of 200,000 people and occasionally tipped over the 250,000 mark in peak years.

In 2010/2011 the department reported that its deportation target was 224,000 but that actual deportations were less than a quarter of that, at 55,825. The report goes on to explain that the deviation was a result of the introduction of the DZP – adding that, previously, Zimbabweans had constituted the bulk of deportations, estimated to be “in excess of 160,000”.

Corey Johnson of the Scalabrini Centre, an NGO focused on furthering the cause of migrants in South Africa, believes the recent deviations are largely down to budgetary constraints.

“I think the wide fluctuations over the years point towards the lack of a clear policy in regards to immigration enforcement/deportation generally – it will be interesting to see if last year's Operation Fiela will result in another spike,” he added.

Operation Fiela was described by the government as “a multidisciplinary interdepartmental operation aimed at eliminating criminality and general lawlessness from our communities.”

While statistics for 2015/16 are not yet available, Jeff Radebe, Minister in the Presidency, claimed that between April and July 2015, 15 396 people were deported as a result of the operation.

Manson Gwanyana from the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) explains that when a police officer or immigration officer encounters someone they suspect to be an illegal immigrant, that person should be asked for papers proving their status. If they have no papers, they may be held at a place of detention for 48 hours while their status is determined.

This verification must be done by a DHA official, and in reality, Gwanyana says, often takes longer than 48 hours, sometimes over a week. Once their status as an undocumented migrant has been verified, they must be given a notice of deportation.

Next, the government must communicate with the deportee’s country of origin to inform them of the deportation. If the person is sent to Lindela, an embassy official must go to the facility to confirm that person is from their country.

“Some embassies [send representatives] there regularly, but officials have complained that some embassies hardly ever visit, delaying the processing of their citizens,” Gwanyana says. “If their country of origin refuses them then they become a person without state, and can be held for up to 120 days but cannot be deported.”

People awaiting deportation cannot be held at any police station prior to moving to Lindela, only those which DHA has identified as places of detention, although Johnson believes that this isn’t always the case. “There have been times when migrants have been held at Pollsmoor and mingled with the general population there, which isn’t supposed to happen.”

Gwanyana adds that while those in Gauteng are typically moved to Lindela within a week, some people spend up to three months at police stations.

Definitive figures regarding the numbers of people at Lindela and their demographics are hard to come by, as the DHA doesn’t release this information publically.

The September 2014 SAHRC Investigative Report into Lindela indicated that on the day of their inspection there were around 1,360 residents, of which around 1,200 (88%) were men. Gwanyana, who is often part of inspections, reports that this year the population has been between 2,500 and 3,000 at each of his visits, with a maximum of around 200 of those residents being women.

The SAHRC report gave a breakdown per nationality for certain countries, with at least 89% being from African countries, Malawians making up 44% of residents.

In February 2016 the Malawian High Commission claimed that Malawians made up 45% of those at Lindela. DHA spokesperson Mayihlome Tshwete also stated at the time that 1,154 Malawians were at Lindela. Gwanyana confirms that these figures are consistent with what he has observed and adds that the consistently large numbers [of Malawians] currently at Lindela might be due to difficulties and expenses in deporting them. Owing to departmental budget cuts, DHA switched from flying Malawians out to bussing them out, but these busses have to travel through other countries en route to Malawi, and other countries aren’t keen to allow them through, causing a backlog.

Johnson notes that pregnant women, mothers with minor children, and unaccompanied minors are not held at Lindela, but must be referred to the Department of Social Development (DSD) and held at places of safety – government-run or non-profit facilities that have been deemed safe and appropriate to accommodate their needs.

Section 41 of the Immigration Act covers conditions for the detention of an individual at Lindela, Gwanyana explains, while Annexure B of the Regulations to the Immigration Act sets out the Minimum Standards of Detention. Additionally, everyone held at Lindela has rights under the Constitution, The National Health Act (No 61, 2003), the National Strategic Plan on HIV, STIs and TB (2012-2016) and the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (No 3 of 2000).

Research by Dr Roni Amit from the African Centre for Migration and Society into human rights violations at Lindela uncovered numerous concerns, including the DHA’s failure to verify detainees’ immigration status, people not being notified of their rights, the correct warrants not being obtained, and people being detained beyond the legal 120 days. Detainees also weren’t getting sufficient meals, and the standards of personal hygiene and medical treatment were unacceptable.

Gwanyana, who participates in the SAHRC’s monitoring visits, says that the department is cooperative in releasing those who have stayed 120 days, but expresses frustration that this isn’t automatically monitored.

Additionally, civil rights bodies must give Lindela 48 hours notice before meeting detainees, and each organisation is only allowed to see five people per day. “So even if I know of thirty people being illegally detained, I can’t get them out this week,” Gwanyana says.

Current critical concerns for the LRC are the detention of minors. “If there is any suspicion around the age of a detainee, the DSD must conduct an age assessment, and if that person is under 18 they must be taken to a place of safety,” he says. The LRC is also concerned about people who are being arrested on entry or after a few days in the country, when they are here to apply for asylum.

A 2014 study by the Institute for Security Studies and the ACMS found a total of R199,9-million was spent by the DHA in 2012/13 on deportation (an increase over the preceding two periods). Dr Amit, who was one of the researchers on the paper, says the numbers were very hard to obtain, but that the amount covered physical costs of deportation, and was separate from the R90.7-million that was spent on Lindela.

In 2013/14 the daily cost per resident at Lindela was R99.41 per person per day, with an average stay of 30 days – or R2.97 million per thousand residents. More detailed assessments of these expenses are impossible Dr Amit explains, as the numbers are “a closely guarded secret”. Currently, Gwanyana says, people are only being deported if they pay for the cost of their own ticket.

The same report found that in the 2013/14 financial year, the DHA spent R13-million on joint deportation operations with SAPS. In 2009, SAPS Gauteng, which accounts for over 50% of arrests leading to deportation, spent over R362.5-million on detecting, detaining and transferring undocumented foreigners to Lindela. No updated figures are available, but Gwanyana believes that there has been no change in the extent to which the police are involved in arresting undocumented migrants.

According to annual reports the DHA had R503.3-million in pending legal claims against them regarding Immigration Affairs in 2013, while claims in 2014/2015 climbed to R581.2 million. The department explains that the claims “arise mainly out of the unlawful arrests and detention of illegal foreigners, as well as damages arising from the department’s failure to timeously make decisions on permits.”

While Gwanyana isn’t able to comment on what this figure might be currently, he blames these costs on DHA inefficiency. “Typically we send letters of demand, then we end up in court, and almost always we don’t argue, they just immediately settle.” Each case like this costs roughly R30,000 in legal fees he says, and could be avoided if DHA responded to the letters.

Edited by Tanya Pampalone and Nechama Brodie

The only facility of its kind in South Africa, Lindela is located in Krugersdorp West about 40 kilometres outside of Johannesburg. It has facilities for up to 4,000 people, with separate areas for men and women. The management of Lindela is contracted out by the DHA to Bosasa, a private facilities management company. In the past few years Lindela has been featured in the news with allegations of bad treatment of foreigners, and human rights violations.

Who gets deported from South Africa and why?

According to the DHA’s most recent annual report, during the 2014/15 financial year 54,169 people were deported from South Africa. This less than half the 131,907 people reported as being deported in the previous year, and lower still than the period prior to 2009, when deportation rates were regularly in excess of 200,000 people and occasionally tipped over the 250,000 mark in peak years.

| Year | Number of people deported from South Africa |

| 2001/02 | 156123 |

| 2002/03 | |

| 2003/04 | 164,294 |

| 2004/05 | 170,301 |

| 2005/06 | 209,988 |

| 2006/07 | 266,067 |

| 2007/08 | 245,294 |

| 2008/09 | 280,837 |

| April 2009 | Introduction of the new Dispensation of Zimbabweans Project (DZP) permits. |

| 2009/10 | 101,060 |

| 2010/2011 | 55,825 |

In 2010/2011 the department reported that its deportation target was 224,000 but that actual deportations were less than a quarter of that, at 55,825. The report goes on to explain that the deviation was a result of the introduction of the DZP – adding that, previously, Zimbabweans had constituted the bulk of deportations, estimated to be “in excess of 160,000”.

Corey Johnson of the Scalabrini Centre, an NGO focused on furthering the cause of migrants in South Africa, believes the recent deviations are largely down to budgetary constraints.

“I think the wide fluctuations over the years point towards the lack of a clear policy in regards to immigration enforcement/deportation generally – it will be interesting to see if last year's Operation Fiela will result in another spike,” he added.

Operation Fiela was described by the government as “a multidisciplinary interdepartmental operation aimed at eliminating criminality and general lawlessness from our communities.”

While statistics for 2015/16 are not yet available, Jeff Radebe, Minister in the Presidency, claimed that between April and July 2015, 15 396 people were deported as a result of the operation.

How does deportation work?

Manson Gwanyana from the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) explains that when a police officer or immigration officer encounters someone they suspect to be an illegal immigrant, that person should be asked for papers proving their status. If they have no papers, they may be held at a place of detention for 48 hours while their status is determined.

This verification must be done by a DHA official, and in reality, Gwanyana says, often takes longer than 48 hours, sometimes over a week. Once their status as an undocumented migrant has been verified, they must be given a notice of deportation.

Next, the government must communicate with the deportee’s country of origin to inform them of the deportation. If the person is sent to Lindela, an embassy official must go to the facility to confirm that person is from their country.

“Some embassies [send representatives] there regularly, but officials have complained that some embassies hardly ever visit, delaying the processing of their citizens,” Gwanyana says. “If their country of origin refuses them then they become a person without state, and can be held for up to 120 days but cannot be deported.”

People awaiting deportation cannot be held at any police station prior to moving to Lindela, only those which DHA has identified as places of detention, although Johnson believes that this isn’t always the case. “There have been times when migrants have been held at Pollsmoor and mingled with the general population there, which isn’t supposed to happen.”

Gwanyana adds that while those in Gauteng are typically moved to Lindela within a week, some people spend up to three months at police stations.

Who is held at Lindela?

Definitive figures regarding the numbers of people at Lindela and their demographics are hard to come by, as the DHA doesn’t release this information publically.

The September 2014 SAHRC Investigative Report into Lindela indicated that on the day of their inspection there were around 1,360 residents, of which around 1,200 (88%) were men. Gwanyana, who is often part of inspections, reports that this year the population has been between 2,500 and 3,000 at each of his visits, with a maximum of around 200 of those residents being women.

The SAHRC report gave a breakdown per nationality for certain countries, with at least 89% being from African countries, Malawians making up 44% of residents.

In February 2016 the Malawian High Commission claimed that Malawians made up 45% of those at Lindela. DHA spokesperson Mayihlome Tshwete also stated at the time that 1,154 Malawians were at Lindela. Gwanyana confirms that these figures are consistent with what he has observed and adds that the consistently large numbers [of Malawians] currently at Lindela might be due to difficulties and expenses in deporting them. Owing to departmental budget cuts, DHA switched from flying Malawians out to bussing them out, but these busses have to travel through other countries en route to Malawi, and other countries aren’t keen to allow them through, causing a backlog.

Johnson notes that pregnant women, mothers with minor children, and unaccompanied minors are not held at Lindela, but must be referred to the Department of Social Development (DSD) and held at places of safety – government-run or non-profit facilities that have been deemed safe and appropriate to accommodate their needs.

What are the legal rights of detainees?

Section 41 of the Immigration Act covers conditions for the detention of an individual at Lindela, Gwanyana explains, while Annexure B of the Regulations to the Immigration Act sets out the Minimum Standards of Detention. Additionally, everyone held at Lindela has rights under the Constitution, The National Health Act (No 61, 2003), the National Strategic Plan on HIV, STIs and TB (2012-2016) and the Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (No 3 of 2000).

Concerns over human rights violations faced by detainees

Research by Dr Roni Amit from the African Centre for Migration and Society into human rights violations at Lindela uncovered numerous concerns, including the DHA’s failure to verify detainees’ immigration status, people not being notified of their rights, the correct warrants not being obtained, and people being detained beyond the legal 120 days. Detainees also weren’t getting sufficient meals, and the standards of personal hygiene and medical treatment were unacceptable.

Gwanyana, who participates in the SAHRC’s monitoring visits, says that the department is cooperative in releasing those who have stayed 120 days, but expresses frustration that this isn’t automatically monitored.

Additionally, civil rights bodies must give Lindela 48 hours notice before meeting detainees, and each organisation is only allowed to see five people per day. “So even if I know of thirty people being illegally detained, I can’t get them out this week,” Gwanyana says.

Current critical concerns for the LRC are the detention of minors. “If there is any suspicion around the age of a detainee, the DSD must conduct an age assessment, and if that person is under 18 they must be taken to a place of safety,” he says. The LRC is also concerned about people who are being arrested on entry or after a few days in the country, when they are here to apply for asylum.

What does detention cost?

A 2014 study by the Institute for Security Studies and the ACMS found a total of R199,9-million was spent by the DHA in 2012/13 on deportation (an increase over the preceding two periods). Dr Amit, who was one of the researchers on the paper, says the numbers were very hard to obtain, but that the amount covered physical costs of deportation, and was separate from the R90.7-million that was spent on Lindela.

In 2013/14 the daily cost per resident at Lindela was R99.41 per person per day, with an average stay of 30 days – or R2.97 million per thousand residents. More detailed assessments of these expenses are impossible Dr Amit explains, as the numbers are “a closely guarded secret”. Currently, Gwanyana says, people are only being deported if they pay for the cost of their own ticket.

The same report found that in the 2013/14 financial year, the DHA spent R13-million on joint deportation operations with SAPS. In 2009, SAPS Gauteng, which accounts for over 50% of arrests leading to deportation, spent over R362.5-million on detecting, detaining and transferring undocumented foreigners to Lindela. No updated figures are available, but Gwanyana believes that there has been no change in the extent to which the police are involved in arresting undocumented migrants.

According to annual reports the DHA had R503.3-million in pending legal claims against them regarding Immigration Affairs in 2013, while claims in 2014/2015 climbed to R581.2 million. The department explains that the claims “arise mainly out of the unlawful arrests and detention of illegal foreigners, as well as damages arising from the department’s failure to timeously make decisions on permits.”

While Gwanyana isn’t able to comment on what this figure might be currently, he blames these costs on DHA inefficiency. “Typically we send letters of demand, then we end up in court, and almost always we don’t argue, they just immediately settle.” Each case like this costs roughly R30,000 in legal fees he says, and could be avoided if DHA responded to the letters.

Edited by Tanya Pampalone and Nechama Brodie

Add new comment