IN SHORT: Claims that South African criminals use a collection of crude symbols to secretly mark houses for burglary are urban legends. There is no evidence that these signs have ever been used, and their origins suggest a long history of exaggeration and false claims.

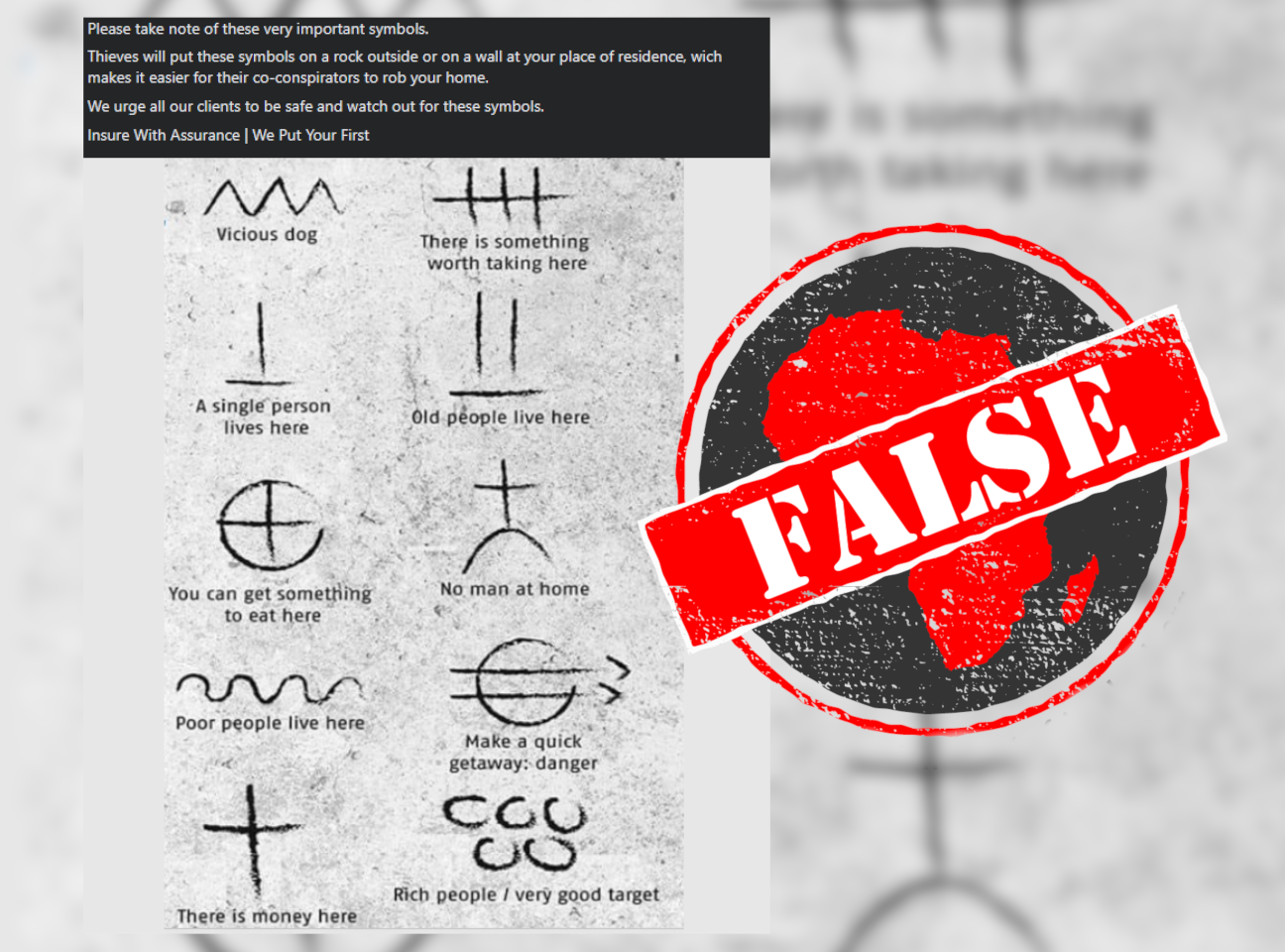

A message shared with Africa Check on WhatsApp claims that criminals use crudely drawn signs as a means of communication, and suggests that everyone should “get familiar with these signs and means of communication among crooks”.

It is one of many similar messages shared on social media sites including Facebook, TikTok and even business networking site LinkedIn.

The posts warn that criminals mark houses they want to break into with symbols whose meanings include “there is something worth taking here”, “vicious dog”, and “rich people/very good target”.

Is there any meaning behind these symbols, and should South Africans be wary of them?

South Africans regularly warned about similar marks, but no evidence they’ve ever been used

South Africans have been warned many times in the past about “signs used to mark houses”, often in social media chain messages, but sometimes by actual news outlets.

In 2014, the Mercury newspaper published an article repeating warnings apparently shared by a police captain. The following year, the Polokwane Review repeated warnings apparently made by a police spokesperson.

However, the official South African police have not released any evidence linking these marks to burglary.

Both articles warn that certain arrangements of stones or types of litter and other markings indicate certain things about a house. But there are many problems with these claims. For one thing, there is no evidence of these signs ever being used.

In an interview with CapeTalk radio in April 2023, anti-crime activist Yusuf Abramjee said that these claims are considered by law enforcement experts to be urban legends.

Abramjee said he suspects the claims start circulating after people make a connection between something like an unusual piece of litter and a subsequent burglary, and warn others to look out for the same “mark”.

However, Abramjee said: “There’s no evidence based on what we’ve seen over the years to prove that your house will be targeted.”

He also discussed the very slim likelihood of modern criminals, with access to cellphones and other reliable means of communication, communicating through crude markings made with litter and debris. These signs would not be helpful to criminals because they could so easily be disturbed, by a pedestrian or the weather.

Researcher Rudolph Zinn surveyed convicted South African house robbers in prison for his 2010 book Home Invasion. Apparently most said these symbols were not common and 80% said that they had never heard of robbers marking houses in this way.

In 2009, a British former burglar told the Guardian newspaper that he had never heard of such a code being used by criminals, despite claims circulating in England at the time. And the fact-checking organisation Snopes debunked these claims when they resurfaced in 2015.

The markings that South Africans are usually warned about are often physical objects, such as empty drinks cans, but the images shared on social media show crude drawings. Are these drawings more likely to be used by would-be burglars? In short, no.

Symbols are possibly apocryphal ‘hobo language’ presented out of context

The symbols shown belong to the “hobo language”, a collection of signs supposedly used by homeless travellers, known as hobos, in the US. Stories of these markings, commonly referred to as the “hobo code”, began in the late 1800s.

According to these claims, the code was used by travellers who wanted to leave advice for others on where to get free or cheap food and lodgings, and which places to avoid. “Translations” of the signs often included meanings such as “kind lady lives here” or “food here if you work”, as well as warnings like “vicious dog here”.

While the hobo code has been included in books, newspapers and magazines for more than a century, as recently as August 2023, there is little evidence that it was ever actually used.

Nonprofit the Historic Graffiti Society says about the code:

Hobo signs were not the secret language of hoboes. While they definitely found a place in folklore, mainly thanks to newspapers throughout the decades, there is little to no concrete evidence to prove their existence. It is possible that a very simple set of signs (good, bad, safe, dangerous) were used by a very small minority of the traveling population, but nothing which ever took hold or was widespread. The real language of hoboes was, and is still to this day, word of mouth.

There is no reason to believe that these symbols, which originated as urban myths in the US in the 1800s, have been adopted by modern South African criminals. As with similar urban legends, there's no need to worry about them being used to target houses for burglary.

Republish our content for free

For publishers: what to do if your post is rated false

A fact-checker has rated your Facebook or Instagram post as “false”, “altered”, “partly false” or “missing context”. This could have serious consequences. What do you do?

Click on our guide for the steps you should follow.

Publishers guideAfrica Check teams up with Facebook

Africa Check is a partner in Meta's third-party fact-checking programme to help stop the spread of false information on social media.

The content we rate as “false” will be downgraded on Facebook and Instagram. This means fewer people will see it.

You can also help identify false information on Facebook. This guide explains how.

Add new comment