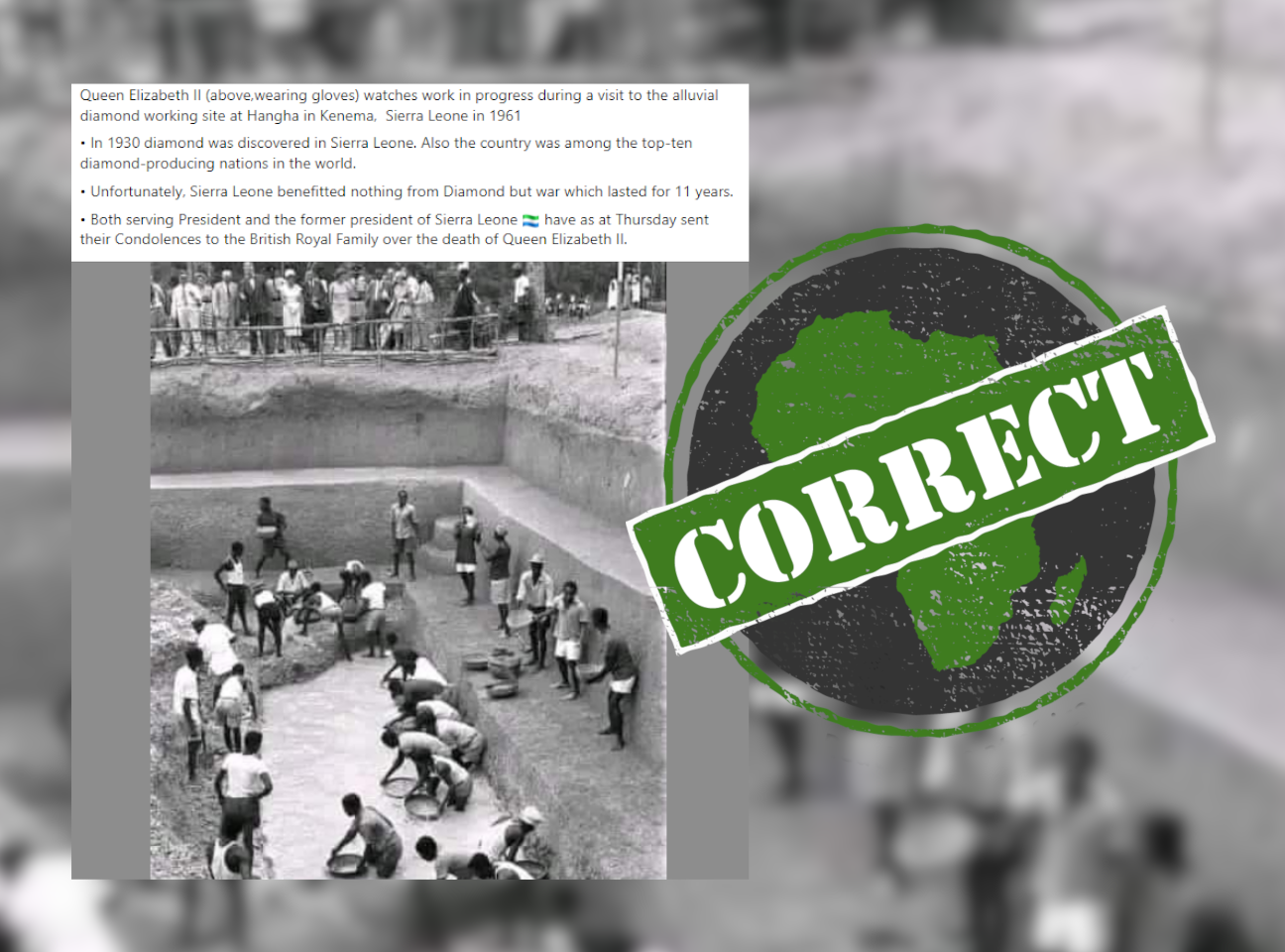

IN SHORT: Elizabeth can be seen in the black and white photo wearing a hat and gloves and holding a handbag. Below her, men pan diamonds from a pool of water at the bottom of a deep pit.

In a black and white photo posted on Facebook in September 2022, labourers work in a pool of water at the bottom of a deep terraced pit. At the top of the pit, a group of well-dressed people stand behind a railing, looking down on the labourers.

“Queen Elizabeth II (above,wearing gloves) watches work in progress during a visit to the alluvial diamond working site at Hangha in Kenema, Sierra Leone in 1961,” the photo’s caption begins.

The United Kingdom’s queen Elizabeth II died on 8 September, aged 96, after 70 years on the throne. She was crowned queen in 1952.

Alluvial diamonds are found in and around rivers and shorelines, having been washed out of the kimberlite rock they were formed in.

Sierra Leone is a small country – about the size of Ireland – on the West African coast. It was the first of what would eventually be the United Kingdom’s many African colonies.

“In 1930 diamond was discovered in Sierra Leone,” the photo’s caption continues. “Also the country was among the top-ten diamond-producing nations in the world. Unfortunately, Sierra Leone benefitted nothing from Diamond but war which lasted for 11 years.”

Since Elizabeth’s death, as with many headline-grabbing events, false information about her has been circulating online.

And Meta’s fact-checking system has flagged the post as possibly false. Meta is the parent company of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp.

Does the photo really show Elizabeth II watching diamond miners at work in Sierra Leone in 1961?

Snapped by British photojournalist Terry Fincher

A TinEye reverse image search of the photo reveals that the post is correct.

The photo is part of the collections of the reputable stock image sites Alamy and Getty Images.

Both sites give the photo the same caption: “Queen Elizabeth watches work in progress during a visit to the alluvial diamond workings at Hangha in Kenema, an eastern province of Sierra Leone, 1st December 1961.”

Getty credits the photo to British photojournalist Terry Fincher, who died in 2008.

In a higher resolution version of the photo on the Getty site, Elizabeth can be seen at the right of the people standing at the top of the pit. She wears a white hat and gloves, and is holding a handbag.

A not-quite-post-colonial tour of West Africa

In late 1961, Elizabeth II visited Ghana, Sierra Leone and the Gambia in a month-long tour of West Africa.

Ghana had gained independence from British colonialism in 1957. In 1961, the Gambia was still a British colony.

Sierra Leone was in a between stage. In 1961 it no longer had British colonial status, but remained a dominion of the crown with Elizabeth its queen and head of state. The country would only become a republic 10 years later, in 1971.

That was more than 200 years after Britain, in 1748, seized an island named Bunce. Bunce island lies in a river north of Freetown, today Sierra Leone’s capital. It was a centre of the trade in enslaved people from West Africa to the Americas.

The island’s importance to the history of the transatlantic slave trade has put it on the World Monuments list and given it tentative status as a Unesco World Heritage Site.

The language spoken by the Gullah community in the southeastern US states of Georgia and South Carolina traces their ancestry directly back to enslaved people taken from Sierra Leone.

Colonisation of Sierra Leone progressed in stages, until it was officially declared a crown colony in 1808.

Diamonds in Sierra Leone

Diamonds were discovered in Sierra Leone in 1930. In 1935, the British colonial authorities gave the De Beers Sierra Leone Selection Trust exclusive mining and prospecting rights over the entire country for 99 years.

By 1937, Sierra Leone was producing a million carats of diamonds every year. One carat is 0.2 grams of diamond, so De Beers was able to take 200 kilograms of diamonds from this one small colony every year.

But because Sierra Leone diamonds are alluvial and so easily mined – they don’t have to be dug out of rock deep in the earth – the country also has a long history of small-scale illegal diamond mining.

By 1956 there were some 75,000 illicit miners operating outside of the De Beers monopoly. According to one account, this led to “smuggling on a vast scale” and a “general breakdown of law and order”.

After independence from Britain, conflict over diamonds continued. In 1991 civil war broke out. The war raged for more than a decade, and saw “intense violence against civilians, recruitment of child soldiers, corruption and bloody struggle for control of diamond mines,” says the International Center for Transitional Justice.

The human cost of diamond conflict in Sierra Leone has even reached Western popular culture, in Hollywood actor Leonardo DiCaprio’s 2006 movie Blood Diamond.

Small-scale or artisanal diamond mining in Sierra Leone continues today. In 2020, De Beers launched its “innovative GemFair programme designed to help formalise the artisanal and small-scale (ASM) diamond mining sector”. The programme would reportedly cover 100 small mines.

But it remains a fact that, as one headline puts it, the “wealth from Sierra Leone’s diamonds” has failed to enrich local communities.

Sierra Leone ranks at 181 out of 191 countries in the 2021/22 Human Development Index, with a score of 0.477. The United Kingdom, by contrast, ranks at 18 out of 191, with a score of 0.929.

The index is put together by the United Nations Development Programme. It assesses progress in “three basic dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living”.

Republish our content for free

For publishers: what to do if your post is rated false

A fact-checker has rated your Facebook or Instagram post as “false”, “altered”, “partly false” or “missing context”. This could have serious consequences. What do you do?

Click on our guide for the steps you should follow.

Publishers guideAfrica Check teams up with Facebook

Africa Check is a partner in Meta's third-party fact-checking programme to help stop the spread of false information on social media.

The content we rate as “false” will be downgraded on Facebook and Instagram. This means fewer people will see it.

You can also help identify false information on Facebook. This guide explains how.

Add new comment