-

Social grants are vital in South Africa. But the president mistook the number of grants for the number of beneficiaries.

-

By using a lower baseline of people employed in 1994, Ramaphosa claimed more progress than has been delivered, while also exaggerating economic growth since then, as inflation has been a key factor.

-

But he was right that a job creation and support programme has created more than 1.7 million opportunities, and that the matric class of 2023 had a record pass rate.

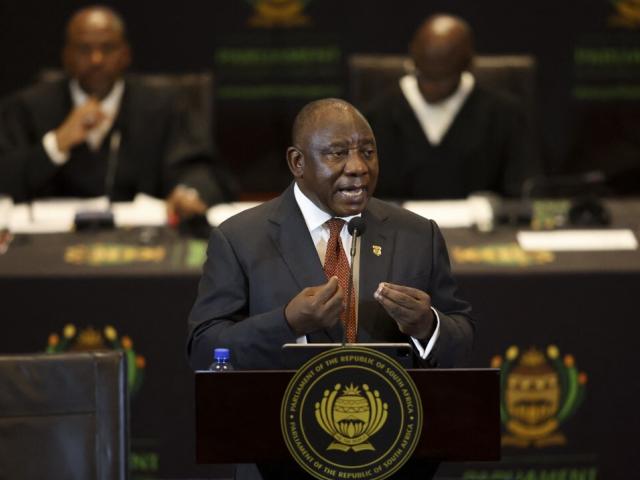

In a marked departure from recent years, South African president Cyril Ramaphosa's eighth state of the nation address started on time, helped in no small part by a boycott by the opposition Economic Freedom Fighters.

With some polls showing the African National Congress (ANC) facing the battle of its political life to retain an outright majority in upcoming national elections, Ramaphosa sought to rally voters by drawing on the party's 30-year record in office.

To do this, Ramaphosa used the life story of "democracy's child" Tintswalo, who the president said was born at the dawn of freedom in 1994. Tintswalo, he said, had benefited from free health care, lived in one of the "millions of houses" built to house the poor, and had access to basic water and electricity that her parents did not.

She had also been enrolled in a no-fee school where she received free meals, was funded by the state through tertiary education and once working, benefited from employment equity and black economic empowerment policies.

But was the president on the money with all his claims of progress? We took a closer look.

Note: We will be updating this report as we continue to compare more of the claims with the facts - so be sure to check back with us.

Social assistance programmes, such as grants, aim to alleviate poverty, reduce economic inequality and ensure a minimum standard of living for individuals and families in need.

The South African Social Services Agency (Sassa) administers and pays out such social benefits, including pensions and child support grants, to citizens.

December 2023 is the last month for which Sassa has published data on the number of grants provided each month. At the end of that month, 13,067,314 child support grants were provided.

The child support grant is the largest social grant, and including other grants, Sassa reported that a total of 18,890,995 grants had been paid out to beneficiaries by the end of December.

There is one grant that is not included here: the Covid-19 social relief of distress (or SRD) grant that has been paid out to beneficiaries since May 2020. A person can only qualify for this grant if they are not already receiving another form of state support.

ESA ALEXANDER / POOL / AFP

Simon Netshifhefhe, Sassa’s senior manager for grants projection, reporting and monitoring, told Africa Check that 7,690,106 SRD grants were paid in March 2023 (the most recently reported data). Combined with the 18,829,716 other grants paid in March 2023, this means just over 26.5 million grants were paid in that month.

But this is only the number of grants paid out. It is not the number of people who received a grant.

Ramaphosa mistakes grants for recipients

While the SRD grant is an exception, some social grant recipients may receive more than one grant. For example, someone could receive both a child support grant as well as a disability grant.

Sassa reported that nearly 19 million grants given in December 2023 went to a total of 11,853,781 beneficiaries. In March, there were 11,744,259 beneficiaries, meaning that a total of just over 19.4 million individuals received a grant in that month.

This is a common error that Africa Check has corrected in the past. As a result of this mistake, Ramaphosa overestimated the number of beneficiaries by more than six million people.

The Covid-19 social relief of distress (or SRD) grant has been paid out to beneficiaries since May 2020. It pays R350 per month to beneficiaries, provided that they do not already receive another form of government assistance.

The grant is also overseen by Sassa but is not reported alongside other grants in the agency’s regular statistical publications.

As reported in the above claim, Simon Netshifhefhe, Sassa’s senior manager for grants projection, reporting and monitoring, told Africa Check that 7,690,106 SRD grants had been paid in March 2023, the most recent data reported.

A higher number of grants (8,452,917) were approved that month, but not all were paid.

This figure is slightly lower than the “8.5 million” beneficiaries given in Sassa’s 2022/23 annual report, suggesting that these figures have since been revised.

Ramaphosa also made this claim during the ANC’s annual January 8th statement on 13 January. At the time, Africa Check rated it as an underestimate as Statistics South Africa’s now defunct October Household Survey estimated there were 8.9 million people employed in 1994.

While that survey has been criticised for under-representing black respondents, it surveyed 30,000 households, and included the nominally independent black “homelands” or Bantustans in national statistics for the first time.

By using a lower starting point, Ramaphosa again exaggerated the progress made since 1994.

The October Household Survey was conducted annually until 1999, when it was replaced by the Labour Force Survey. According to the latest release from Stats SA, covering July to September 2023, an estimated 16.745 million people were employed.

But comparing this figure with historical employment numbers was not straightforward, Dr Neva Makgetla, senior economist at the Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies research institute, previously told Africa Check.

She explained that while the raw number of employed people had increased, so had the working-age population, from 24.6 million in 1994 to 40.9 million in 2024. A more accurate way of looking at the situation, Makgetla said, was in terms of the ratio of those in employment to the working-age population. The ratio was 41% in 2023, roughly the same as in 1994.

The size of a country’s economy is often measured by its gross domestic product (GDP). This is the value of all the goods and services produced in a given period, usually a year.

The World Bank has data on South Africa’s GDP going back to 1960.

It shows that the country’s nominal GDP, which does not take into account inflation over the years, grew 2.6 times from US$153.51 billion in 1994 to $405.27 billion in 2022. (Note: 2023 GDP figures are not yet available.)

But it’s important to separate real economic growth from inflation.

World Bank data based on constant or real GDP (which removes the effect of inflation) shows that the country’s economy grew 1.9 times from $187.38 billion in 1994 to $360.71 billion in 2022.

The Presidential Employment Stimulus (PES) was launched in October 2020 to mitigate the economic damage of the Covid-19 pandemic. The programme provides funding for the creation of new jobs and financial support for jobs and livelihoods that would otherwise have been lost.

The most recent update of the programme, published in February 2024, says that it has provided 1,762,749 “jobs and livelihood opportunities” since inception.

It is not clear how many of these are new jobs, as the PES website does not yet include a breakdown of the recently released update.

Kate Philip, programme lead for the PES initiative, told Africa Check that the website was “about to be updated” to reflect the latest data.

Ramaphosa said that internet access had “risen dramatically” over the past decade and gave figures to support his claim.

Stats SA tracks internet access in its general household surveys. The latest survey shows that 34.4% of households had access in 2011. By 2022, the figure had increased to 75.3%.

These figures include access by any means, such as through work, public wifi, internet cafes and educational facilities.

The percentage of households with internet access at home was 10.2% in 2011. By 2022, it had risen to 13%. As Stats SA points out, this percentage “remained relatively stable between 2010 and 2021”.

The department of basic education’s National School Nutrition Programme aims to provide one meal a day to all learners in poorer primary and secondary schools.

According to the department’s 2022/23 annual report, the programme reached 9,689,300 learners in 21,156 schools.

This is in line with data from Stats SA’s 2022 General Household Survey, which shows that the programme reached 9,630,775 learners that year.

Ramaphosa missed the opportunity to claim a higher figure.

A total of 691,160 South African grade 12 learners sat the National Senior Certificate (NSC) examinations, also known as matric exams, in 2023.

Of these, 572,983 passed and received their school leaving certificates. This is a pass rate of 82.9%.

Announcing the results in January 2024, basic education minister Angie Motshekga said the class of 2023 had “made history”.

She said the number of students who passed was the second highest in history (580,555 students passed in 2022), but when expressed as a percentage of all those who wrote, the 2023 pass rate was the highest.

This is shown in a table published in the basic education department’s 2023 technical report.

Previously, the class of 2019 held the record for the highest pass rate (81.3%).

The bachelor pass rate in 2023 was 40.9%, meaning that just under half of the students who sat the NSC exams qualified to study at university.

As evidence of progress in the education sector, Ramaphosa said that fewer learners were dropping out of school.

Reducing the dropout rate has been a priority for the department of basic education (DBE). The department calculates the dropout rate by subtracting the percentage of learners who completed the previous year’s grade from the percentage who enrolled in the following year’s grade. For example, if 70% of the learners who passed grade 5 enrol in grade 6, the dropout rate for grade 5 would be 30%.

Some analysts and opposition politicians have calculated the dropout rate by dividing the number of learners who completed matric by the number who entered grade one 12 years earlier. For example, of the 691,160 learners who sat the 2023 national school-leaving exams, 572,983 obtained their national senior certificates – a pass rate of 82.9%. However, the number of learners who started grade 1 in 2012 was 1,208,973. This means that less than half of the learners who started grade 1 in 2012 went on to matriculate in 2023.

This type of calculation has often been referred to as “the real matric pass rate”. However, Africa Check has previously written about the shortcomings of using the number of learners in the early grades to calculate a dropout rate.

In South Africa, the key years in a cohort’s school career are the completion of grade 7, which is the level the country’s education department uses as a measure of literacy; grade 9, the final year of compulsory education; and grade 12 – the completion of the cohort’s basic education. The graph below shows trends in the pass rates for each of these grades starting from 2002 to 2021.

Source: DBE Annual Performance Plan 2023

The graph, which uses data from Stats SA’s general household surveys, shows that the number of learners passing these grades is increasing.

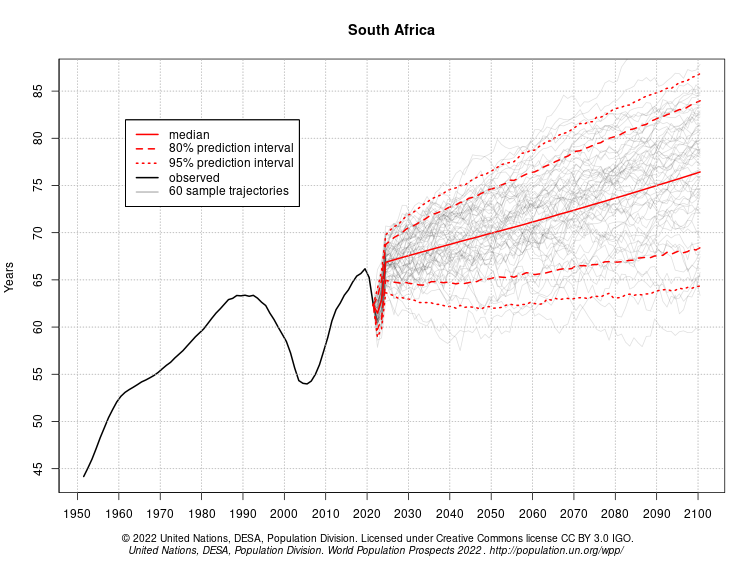

Ramaphosa took pride in the dramatic increase in life expectancy, saying that South Africans were now living longer than ever before.

There are several sources of data on life expectancy. Most use “life expectancy at birth” as a measure. This is an estimate of the number of years a person born in the reference year can be expected to live. Life expectancy changes over a person’s lifetime in response to pandemics, advances in healthcare, and other health influences.

For this reason, life expectancy at birth is the standard measure, unless otherwise stated, Diego Iturralde, Stats SA’s chief director of demography and population statistics, told Africa Check.

South Africa’s health department uses estimates from Stats SA. The latest data shows that life expectancy has increased from 55.1 years in 2003 to 62.8 years in 2022. Estimates for 2023 are not yet available.

Iturralde said he wasn’t sure where Ramaphosa’s 2023 figure came from, but it wasn’t an official statistic. “I am sure that it is not yet at a level of 65”.

The last World Health Organization life expectancy estimate for South Africa was 65.3 years. But that was in 2019, before the Covid pandemic. Deaths caused by the pandemic significantly reduced life expectancy in South Africa and around the world. The earliest year for which the WHO has data is 2000, when life expectancy was estimated at 55.8 years.

The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN Desa) estimates South African life expectancy at 62.89 years in 2023 and 66.87 in 2024 (up from 54.33 in 2003). These estimates are projections.

They are broadly in line with the figures given by Ramaphosa. But if we take a longer view of life expectancy, the picture is not as rosy.

Effects of the HIV/Aids epidemic

Graphs of life expectancy in South Africa, such as this one from UN Desa, show that life expectancy fell dramatically between the early 1990s and the mid-2000s, before rising again until the start of the Covid pandemic in 2020.

Similarly, the latest version of the Thembisa model, another source of demographic statistics, estimates that life expectancy fell from a peak of 63.2 years in 1990 to 54.4 years in 2003.

These changes in life expectancy coincide with the HIV/Aids epidemic in South Africa. The human immunodeficiency virus (or HIV) is a virus that attacks the immune system, causing a syndrome known as Aids (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). It is currently incurable, but can be managed with antiretrovirals (ARVs), which are drugs that prevent the virus from replicating.

The epidemic was worsened by former South African president Thabo Mbeki, who denied the link between HIV and Aids and restricted access to ARVs during his presidency. One study has estimated that Mbeki’s policies caused more than 330,000 preventable early deaths.

By using 2003 as the year of comparison, Ramaphosa skipped over the sharp decline in life expectancy figures that took place before that date.

This report is produced as part of the work of a South African election coalition. In the run-up to the 2024 national elections, the coalition aims to ensure that the claims made by those in charge of state resources and delivering essential services are factually accurate. As voters head to the polls, it is increasingly important that they are able to make informed decisions.

In times like these, you should rely on Africa Check for the facts!

We depend on donations to bring you quality, fact-based information and keep public figures accountable.

Support trusted sources of information

Add new comment